Soundwalking is not new, but it is an activity that many of my undergraduate students have not encountered. In its purest—or purist—form, it is a fairly simple idea: a person walks, and while walking, they listen attentively to the surrounding environment. Soundwalking can be experienced individually or as a group, and reactions to sounds in an environment often result in an increased awareness of both the self and the world.

On the surface, soundwalking may seem both straightforward and an ideal teaching tool. It’s not difficult to do, and the increased sense of awareness it promotes is usually positive. But the further we dig into soundwalking, the more complexities arise. Soundwalking can be used superficially, as a simple exercise to encourage active listening, or it can lead to deep considerations of community, representation, history, and technology. For students with or without musical backgrounds, reflecting on how they hear a particular space while learning about its people and past readily yields several points for critical discussion.1

In Soundwalking through Time, Space, and Technologies (2023), artist and scholar Jacek Smolicki asks, “How can we turn soundwalking from being innocent into a more critical practice, a technique for reconsidering how we, individuals and human collectives, situate ourselves in and account for surrounding

environments?”2 Although Smolicki is speaking about critical approaches to soundwalking in general, I turn his question toward technologically mediated soundwalks with my undergraduate students—an easy stretch for the digital natives of Generation Z.3 Along with my own pedagogical experiences, this article incorporates findings from an IRB-approved study with students in my general-education course on music and the environment (fall 2023). I argue that considerations of technological mediation in soundwalks should not be framed as a straightforward binary construction regarding the presence or absence of technology.4 Indeed, there is significant value in facilitating discussion of the nuances of technological mediation in soundwalking in undergraduate teaching.

Following a section that draws on two earlier publications in this Journal to describe soundwalking in the university classroom, I offer a brief history of soundwalking while in the process problematizing the role of technological mediation in soundwalks. Both sections reveal the multifaceted nature of soundwalking, which resists any easy binaries. The second half of this article presents a two-part case study. To provide an example of how an artist may approach technological mediation and how listeners might respond, I first describe Ellen Reid’s SOUNDWALK, a GPS-enabled soundwalk available in select public parks, by means of an autoethnographic reflection.5 Then, using my autoethnographic account of Reid’s SOUNDWALK as a launchpad, I analyze student responses to questions about technologically mediated soundwalking. To prepare for discussion, my students considered how soundwalks are defined, how artists may approach mediation in soundwalks, and how users may also engage with processes of mediation.

Soundwalking in the University Classroom

In their 2017 article “Resounding the Campus? Pedagogy, Race, and the Environment,” Amanda Black and Andrea Bohlman acknowledge soundwalking as a “canonic exercise” for undergraduates, pointing to its prevalence as an accepted and regular activity in academic settings.6 Instructors of music-centered courses such as ecomusicology, composition, acoustics, and media studies commonly include soundwalks in their syllabi.7 While Black and Bohlman applaud the accessibility of several open-access syllabi that include soundwalks, they also criticize several of these examples for not providing adequate space to discuss difference, diversity, or privilege.8 In particular, Black and Bohlman maintain that many instructors use soundwalking as a supposedly unbiased introduction to “learning how to hear.”9 Students are often encouraged to listen more intently to their immediate environment, observing sounds they may usually fail to notice:

Soundwalks, like so many immersive or experimental collective performances that invite reflection on the unremarkable, have tended to take as their mission some kind of rehabilitation or reboot. They frequently draw attention to that which is ignored, whether animal, vegetable, mineral, or vibrational.10

As the authors note, the resulting binary construction of perceiving/not perceiving, whether of aural or visual stimuli, is problematic, not least because it’s too simplistic. An instructor may encourage student discussion by asking why patterns of perception may occur, but Black and Bohlman suggest that soundwalks can spur conversation about far more complicated issues. They assert that soundwalks can—and should—be used to explore the intersections of history, race, performance, and environmental awareness.11

Indeed, soundwalks occur on lands and in spaces that do not always have neutral histories and meanings, a fact compellingly demonstrated by Black and Bohlman’s Beyond the Belltower project. This project at the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill included nine soundwalk scores “inspired by research in the University Archives that focused on the themes of race, access, and violence within institutional history.”12 Because UNC-Chapel Hill has many sites historically connected to slavery, racism, and activism, Black and Bohlman explain that every score, which is tied to a specific location, either “hosts or hides Black history.”13

Seeking to provide not a model product but a model of process to emulate, Black and Bohlman emphasize the importance of cultivating dialogue between instructors and students, members of peer or colleague groups, and university and community partners when designing and producing a soundwalk.14 By fostering activities that have “the potential to reposition listening as a collective exercise in [a] music (history) classroom” and linking “community and collective action,” soundwalks can be not only richly site-specific but also historically informed and care-oriented.15 Moreover, developing a soundwalk with an emphasis on process helps to create space for creativity, curiosity, self-critique, and even humility—all characteristics that we seek to instill in students.16

Shortly after Black and Bohlman’s Beyond the Belltower, a similar project, titled Sonic Histories, was developed at Western Carolina University (WCU). Sonic Histories

sought to map the intersection of sonic and physical spaces on campus and their impact on the emotional and somatic experiences of students. . . . Moreover, Sonic Histories challenge[d] WCU’s triumphant narrative of progress by curating a lesson which gave students the time and space to actively listen to the sounds of inclusion and exclusion on their own campus.17

The walks were designed for small groups of ten to fifteen participants and guided by a student leader who distributed a portfolio of historical documents from the WCU Libraries’ Special Collections department. Participants were invited to use these documents to reflect “on the erased/contested sites under consideration, with specific attention to race, class, gender, (dis)ability, and belonging on campus.”18 After each soundwalk, a student leader led a fifteen-minute open discussion, which was recorded and later transcribed. Qualtrics surveys were also distributed both before and after each walk to gather additional written feedback.19 Like Beyond the Belltower, Sonic Histories engaged with issues of history and race, albeit in a more qualitative manner.20

The incorporation of technology has further impacted how soundwalks are now designed, experienced, and perceived. While advocating for increased engagement with the digital humanities, Kate Galloway points to the rise of digital media in her article “Making and Learning with Environmental Sound,” asserting:

As digital media becomes more common in today’s reading, writing, performance, outreach, and researching practices, acts of making, tinkering, and explorative play with analog and digital technology, especially sound technologies, are a valuable inclusion to the graduate and undergraduate music history classroom.21

Although Galloway is speaking more generally about embracing technology in music history pedagogy, she quickly pivots to the topic of soundwalks. In two of her courses, students are responsible for designing, recording, and editing at least one soundwalk and one sound collage, which are then uploaded to a public website.22 Students develop their work with a broad audience in mind, aiming to “convey sound studies and music history research” while also considering “the political stakes in producing research intended for public use.”23

Along with the conceptual expansions offered by Beyond the Belltower, Sonic Histories, and Galloway’s students’ public-facing sound projects, curated soundwalks can incorporate multiple audio components: for instance, field recordings, spoken text, musical excerpts, or a combination of these sources. Designing such soundwalks requires technological mediation on both the creative side and on the part of the soundwalker; the curator may record, edit, and mix sounds while the soundwalker will require playback devices to host, play, and hear the audio components. Taking the successful navigation of the various technological components for granted, such mediated soundwalks may also “interrogate our technologized interactions with sound and place when recorded soundscapes are analyzed and then communicated through research or community soundwalk activities.”24 Engaging with these kinds of issues moves well beyond the simple yes-or-no questions about whether or not technology may be used in a soundwalk. For starters, why should technology be used to represent a given space? What can technology help to reveal about a given community for listeners? How does technology push against—or perhaps enhance—one’s understanding of the history, culture, or politics of a given place? It is imperative that instructors who incorporate soundwalking in their courses provide opportunities for students to reflect on the roles technology might play, not merely in soundwalking activities but in their own broader engagement with mediated content. Technology, as we know, is not neutral.

Technologically Mediated Soundwalks, from Then to Now

The group most closely associated with early soundwalking, the World Soundscape Project (WSP), began using soundwalking practices with varying levels of mediation in the 1970s. Lauded by many as launching the field of acoustic ecology, the WSP is not without its critics. Still, the WSP inspired many artists with their soundwork, and there is a rich history of soundwalking that starts with the WSP and leads to present-day practices. Today, mediated soundwalks, enabled by the explosion of technological capabilities in the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries, present critical questions likely unanticipated by the WSP. The following brief examination of the use of technology in soundwalks from the 1970s through 2025 reinforces my two previous assertions: 1) the use of technology in soundwalks is not an either/or binary proposition, and 2) a deeper critical engagement with mediated soundwalks is needed.

Hildegard Westerkamp, a foundational proponent of soundwalking, seems to define the practice as an unmediated experience. In “Soundwalking as an Ecological Practice,” she writes:

Simply put, a soundwalk is any excursion whose main purpose is listening to the environment. It is an exploration of our ear/environment relationship, unmediated by microphones, headphones and recording equipment. It is an exploration of what the “naked ear” hears and how we relate and react to it.25

I regularly show this definition to my students at the beginning of our soundwalking unit, emphasizing that in this particular essay, Westerkamp excludes technology from the experience. Her description aligns with how I introduce my students to soundwalking: we focus on close listening without technological intervention for the first session of the unit. Yet Westerkamp herself produced soundwalking radio broadcasts in the late 1970s and began to create sound collages around the same time.26 She was certainly not a zealot for unmediated soundwalking or unmediated soundscape practices. As my students move further into the soundwalking unit, I add examples of Westerkamp’s work that explicitly involve mediation to encourage students to notice tensions between her technologically mediated and unmediated work.

Such tensions are significant to note, as the history of soundwalks has not progressed linearly from an absence to an inclusion of technological mediation.27 Indeed, Westerkamp and the WSP promoted both mediated and unmediated modes of listening. On one hand, a primarily improvised mode of unmediated soundwalking often served as the first step for members of the WSP as they studied a soundscape. Soundwalks were recorded to assist in “documenting changes in sonic environments and raising awareness to growing noise pollution.”28 Many of the WSP’s public-facing materials, on the other hand, were clearly technologically mediated. In 1972, WSP members Howard Broomfield, Bruce Davis, and Peter Huse began making recordings around Vancouver.29 The following year, the WSP released The Vancouver Soundscape, a double LP with a companion book, based on the recordings by Broomfield, Davis, and Huse.30 That same year, Davis and Huse set out across Canada to record sound environments, the outcome of which was Soundscapes of Canada, a ten-episode radio program that premiered on CBC Radio in October 1974.31 A few years later, in 1978, Westerkamp premiered her weekly radio program, Soundwalking, on Vancouver Co-operative Radio.32

Although the WSP faced some criticism, their work inspired further projects.33 Other artists designed soundwalks, many of which incorporated various forms of technological mediation.34 For instance, the World Ear Project, first broadcast out of Berkeley, California in August 1970, was an outgrowth of the WSP’s work.35 It included broadcasting soundwalks recorded in a variety of locations, and this work continued through the middle of the 1980s.36 Musicologist Michael Palmese provides one particularly rich example from its broadcasts:

[Charles] Amirkhanian [a radio producer in Berkeley] produced a special soundwalk of his own for live broadcast on the World Ear Project in June 1985 while on location with the German composer Stephan Micus in Mundraching, a Bavarian town outside of Munich. The broadcast begins in a remarkable fashion, as the initial sounds of the idyllic landscape are abruptly shattered by the sound of a sonic boom from a passing fighter jet. What results from this coincidence is a conversation between Amirkhanian and Micus on the American military presence in West Germany, nuclear weapons, and how army maneuvers and materiel affect the local community, particularly in the small nearby town of Landsberg.37

Not only is this soundwalk mediated through both its recording and subsequent broadcasting, but it also addresses political and cultural concerns connected to the location of the soundwalk. In this instance, the initial technological mediation (i.e., recording equipment) facilitates dialogue in the field about international and local relationships which is then broadcast using another form of technological mediation (i.e., radio), enabling listeners to have a more nuanced understanding of American and German military concerns.

Janet Cardiff’s The Walk Book (2005), which compiles her work with George Bures Miller from the 1990s and early 2000s, offers another compelling example of technological mediation in a soundwalking project.38 The book describes creating different components for what Cardiff calls “audio walks,” presents contextual framing for several of these walks, and provides visual images and an accompanying CD for listeners to more fully experience the mediated walks.39 According to Cardiff’s website, which may be more readily accessible to some readers than The Walk Book, during an audio walk,

[a]udiences are given an iPod and headphones and the recording guides them through a narrative of events that occur along a route. The audio playback is layered with various background sounds all recorded in binaural audio which gives the feeling that those recorded sounds are present in the actual environment.40

This description clearly indicates that technology is obligatory at all points of the project—during Cardiff’s initial creative and developmental stages as well as for the soundwalker engaging with the final product. The Walk Book itself relates more of Cardiff’s process:

The artist has already experienced the space that the participants visit. She has infiltrated the site and captured its sounds and then she plays them back later [superscript above text: in a different form]. Having observed the environment and taken note of the patterns of movement there, she can anticipate what might happen to us when we visit this place later, what we might see, hear, and feel.41

In addition to the sounds of the site itself, Cardiff weaves her own voice, other voices, and auxiliary sounds into and out of the audio recording.42 Her voiceovers include “observations, reflections, and reminiscences, interlaced in the manner of a stream of consciousness.”43 Such layering provides valuable material for listeners to dissect and consider, but more important for my purposes in this article is the fact that this aspect of the listener’s experience could not exist without audio-editing technology.

Just as technological mediation was frequently employed in the first three decades of soundwalking, contemporary sound artists continue to incorporate one or more types of technology in a soundwalk. However, technological mediation constitutes merely the starting point of the creative processes for several of these soundwalk artists. Because many mediated soundwalks interfere with the sonic environment in which they take place—not only by including additional sounds, but by using sounds that were gathered, arranged, and perhaps manipulated from and in other places—Tim Shaw acknowledges that “technological and compositional process are often removed from the listening experience.”44 As such, listeners are not necessarily aware of which sounds an artist may have collected, let alone changed, or why artistic choices were made. Listeners are plunged into a curated environment in which “clear distinctions between audience and performer, composer and listener” have been created.45 Unless they reveal their artistic choices and processes to listeners, only the sound artist/performer can truly understand the work. For this reason, Shaw champions rendering transparent as many technological processes as possible in works involving soundwalking.

Composer Matthew Burtner scrutinizes the intended purpose of audio-recording equipment in creating soundwalks, noting that recorded elements that might be folded into a soundwalk risk giving “the false impression that the most important sonic aspect of the adventure is contained in the audio sample.”46 In reality, Burtner argues, a recording only offers “acoustic residue”; it cannot substitute for the experience of listening in a particular place.47 Shaw takes his analysis one step further, arguing that soundwalks that incorporate curated sound—particularly sound that pushes a narrative—risk fictionalizing an environment.48 In contrast, interdisciplinary artist Jacek Smolicki is concerned with the impact that the abundance of modern technologies may have on soundwalking vis-à-vis the practice’s originally intended purpose. He questions the extent to which technologies such as microphones, headphones, hearing aids, and cochlear implants “disrupt that ‘most direct aural involvement’ that WSP scholars saw as the fundamental aspect of soundwalking.”49 And then he ponders, conversely, “to what extent can technologies facilitate this access?”50

Smolicki hits an important issue straight on the nose. When is technology a benefit in soundwalking? When may it be a detriment? Hearing aids and cochlear implants, for instance, increase accessibility for people with varying aural abilities, an effect generally accepted as positive. Galloway also points to the benefits of simply recording and relistening to soundwalks, which can lead to “examining how the microphone registers place differently than the human ear.”51 Microphones and headphones can also be used to curate a specific kind of listening experience and may therefore draw more people into more careful modes of listening—a positive impact. And yet, if we are to circle back to Shaw’s concerns about the fictionalization of sound, we can see how technological mediation inevitably distorts the aural environment, an effect that could be construed negatively.

More specifically, although editing and mixing practices may help to create a sonically pleasing recording of or guide to a soundwalk, such technological interventions effectively change the sound of an original field recording, giving preference to what the artist chooses. These choices might be innocuous, such as the shortening of a long recording or gradually fading into a recording to ease the listener into the soundscape. But an artist could also adjust placement and volume levels to impose a false narrative on the soundwalk experience or create a false representation of it; bringing certain sounds to the forefront or pushing certain sounds to the background could ultimately provide a “dishonest” portrayal of the soundscape. Westerkamp herself alludes to this particular pitfall in her Kits Beach Soundwalk.52

The manipulation of the aural experience of a soundscape could pose still additional problems—ethical ones. Does the editing or mixing of sounds create an inaccurate representation of the communities residing in the soundwalk area? Does the soundwalk or its recording effectively obscure troubling histories in a location? In what ways might a soundwalk serve a political agenda or perhaps further issues of inequality? In fact, the use of technology alone can exacerbate disparities. Only those with ready access to a smartphone, tablet, or computer and a pair of headphones can participate in a technologically mediated soundwalk. Given the costs of these devices, such technological requirements risk impeding or excluding the involvement of some listeners. Taken together, the critical questions about mediated soundwalks raised by several soundwalk artists themselves move far beyond the binary choice to use or not to use technology, shifting clearly into an engagement with individual and community values. And there are still more questions to ask! What is the purpose of a particular soundwalk? Is it to walk? Is it to listen? Is to educate? Is to entertain? If listening is paramount to the experience, then what is the listening objective of a technologically mediated soundwalk? What is supposed to be heard, exactly? While I have my own personal responses to these questions, I certainly do not have definitive answers. But as I demonstrate in the following case study of Ellen Reid’s SOUNDWALK, engaging with multiple responses to such questions and embracing diverse viewpoints may help to move soundwalking in the critical and analytical directions for which many scholars and artists advocate.

Case Study: Reid’s SOUNDWALK, Context, and Autoethnography

To explore how such deliberations might further develop and transpire, I incorporated Ellen Reid’s SOUNDWALK into a general-education course I teach on music and the environment. During my experiences of Reid’s SOUNDWALK in two locations in the summer of 2023, I thought repeatedly about technological mediation. I considered my own listening habits—particularly my own binary assumptions about technological mediation—and issues of sound and place. After I completed my first experience of SOUNDWALK, I knew I wanted to solicit additional minds and voices to engage with my reflections and queries. My incoming students (fall 2023) offered an ideal opportunity to do so. What could we learn by diving into this specific soundwalk together?

Before jumping into my experience, let me describe Reid and her work. Reid is an American composer, perhaps most widely recognized for winning the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 2019 for her opera, p r i s m.53 Reid debuted her SOUNDWALK a year later, in 2020, although she had devised the work’s concept years prior.54 According to her SOUNDWALK website, “Ellen Reid SOUNDWALK is a GPS-enabled work of public art that uses music to illu minate the natural environment. . . . SOUNDWALK is user-guided: the path you choose dictates the music you hear.”55 In summer 2023, I experienced SOUNDWALK in two locations: in Dublin in St. Stephen’s Green (June 2023) and in London in Regent’s Park (July 2023).56 SOUNDWALK is multisited, so while one uses the same app in each location to listen to Reid’s sounds, ideally through headphones, each location has a unique pairing of Reid’s sounds with GPS coordinates.

Reid’s SOUNDWALK began receiving attention from major news outlets in the fall of 2020 as she launched the project in its Central Park location (New York City).57 In addition to publicizing her SOUNDWALK, news coverage described the composed elements that Reid included in the piece. For example, NPR revealed that Reid wrote twenty-five musical “cells” that were inspired by nature. She wrote these initial cells in June and July of 2020. Musicians recorded their parts remotely in August, and then Reid and an engineer mixed the recordings together.58 Finally, Reid and a sound designer walked through Central Park to “beta test where and how the music [would be] triggered.”59

As SOUNDWALK expanded to more locations, Reid’s catalog of sounds expanded, too. For the Griffith Park location in Los Angeles, for instance, Reid used more than one hundred cells. Geotagged to specific locations, the cells vary in timbre and length.60 The Los Angeles Times reported, “as visitors move through [Griffith Park], they wander into and out of musical cells, like sonic zones. And, depending on the pace visitors keep, they’ll hear different parts of a cell at different locations along the walk.”61 This means that no two walks, even at the same location, are the same.

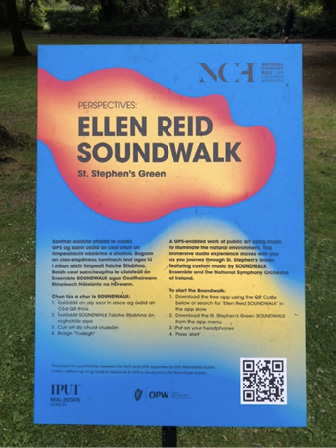

When experiencing a Reid SOUNDWALK, participants are instructed to connect headphones to their devices in order to hear Reid’s musical cells through an app. In colorful plaques posted around St. Stephen’s Green (Dublin), a photograph of which is presented in figure 1, there were four simple directions: download the Ellen Reid SOUNDWALK app, download the St. Stephen’s Green SOUNDWALK, put on your headphones (my emphasis), and begin your walk.62 In a Los Angeles Times article from February 2021, Reid describes her SOUNDWALK as an activity that is meant to be “phone-in-pocket” but that “you’re supposed to hear your footsteps.”63 Headphones are key, but they should not be the sole source of aural information.

A tension between recorded and environmental sound struck me immediately in St. Stephen’s Green. I quickly jotted down some notes in my journal near the beginning of my walk, documenting my listening experience:

[SOUNDWALK] seems to mask some sounds—it’s a richer experience when it’s quieter and I hear the world around me. I can’t not hear the music. I’m trained to hear it first. While the music plays, I do hear birds, dog collars jingling, traffic, and construction, but I miss the smaller sounds—footsteps, rustling, breathing.64

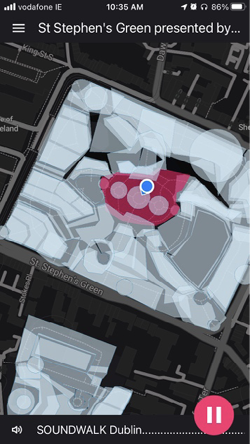

Continuing around St. Stephen’s Green, I eventually made my way to the middle of the park, where there is a series of round structures, represented by five circles in the middle of the map in figure 2.65 In the image, this middle section of the park is highlighted in pink, and my location is indicated by a blue dot. I noted intensifying percussion from the app while in this area, and I marked the presence of low drones, a rhythmic ride cymbal, and a drum set in my journal. I also wrote:

Now [I’m] 100% NOT listening to environment, but [I’m] still interacting with structures in [the] environment; so [I’m] not listening to the environment, but still aware of it and searching for meaning.64

I wanted to remain open to the experience, but I became frustrated by the feeling of being aurally disconnected from the park. While I valued the visual connection that I had established to St. Stephen’s Green, I did not want my only meaningful relationship to the park to be visual. That felt antithetical to the act of soundwalking.

It’s clear that headphones are crucial to the success of Reid’s SOUNDWALK; yet, when a person uses headphones, whether for music, podcasts, or other media, it is easy for recorded sounds coming through the headphones to cover sounds coming from the external environment. Volume, and in particular the delicate act of balancing the volumes of inner (headphones) and outer (park) soundscapes—both of which form central aspects of SOUNDWALK—is a challenge. One can quickly become focused on music or voices coming through the headphones, especially if the app’s volume is turned up loud or if the volume of a musical cell increases. The latter happened to me with the percussion in the middle of St. Stephen’s Green.

When my students complete soundwalks in an unmediated fashion, sans headphones, smartphones, or other devices, they often raise a similar issue. Many of them admit to walking around campus with headphones in their ears, oblivious to the sounds of the surrounding environment. When they remove their headphones for their soundwalk, they frequently reassess their listening habits and notice a completely different soundscape.66 They often remark in class or in written observations that they have neglected to give sufficient attention to sounds—and sometimes significant sounds—because they are focusing primarily on the media flowing through their headphones.67

While they may not explicitly say as much, my students seem to recognize the power and appeal of their personal devices—usually a smartphone—and the forms of mobile listening these devices afford. Their observations of their own behavior echo research by sound studies scholar Michael Bull in his book Sounding Out the City (2000). Many of my students readily admit to using their smartphones to create their own soundworld, which is set apart from the environment in which they are walking or commuting to/from campus. In the first chapter of his book, Bull succinctly writes, “mobility is inscribed into the very design of personal stereos, enabling users to travel through any space accompanied by their own ‘individualized’ soundworld.”68 He articulates a similar idea in one of the final chapters: “The mobility of personal stereos enable[s] users to maintain contact with their favourite types of music around which aspects of their own social identity, orientations and interests are formed and constituted.”69 Although Bull is writing about the Walkman personal stereo, today’s smartphones are utilized similarly.70 Users are able to take their smartphones nearly everywhere, and they largely have control over what they hear. My students often affirm that they, like the listeners in Bull’s study, choose music or other audio content to influence their daily, or even hourly dispositions. Their choices are conscious, and their selected audio often intentionally masks or blocks sounds emanating from public places.71 My students’ behaviors are not new.

Yet listening in this way creates a situation in which listeners can retreat into or become isolated in worlds of their own making. Bull suggests that “switching off [a personal stereo] becomes tantamount to killing off [a listener’s] private world and returning them to the diminished space and duration of the disenchanted and mundane outside world.”72 In other words, emerging from one’s own curated soundworld may be more than just undesirable—it may feel risky, dangerous, or worse.73 While I have experienced my own displeasure at pausing audio to deal with an issue in the “real” world, Bull’s assertion seems slightly overstated. I do not doubt that he is basing this comment on his research interviews, nor do I think he is misrepresenting his subjects. But I would counter his claim with two observations: first, in many instances, listeners do easily return to their private world at a later time; and second, the outside world is not always disenchanting or mundane to listeners. My students have assured me that both of these are true. In fact, they have repeatedly reported that taking a unmediated soundwalk is one of their favorite activities of the semester. Many of them enjoy simply “unplugging” from technology.

This echoes my own experience while engaging with Reid’s SOUNDWALK. After my initial walk in Dublin, I decided to “unplug” myself from my headphones in the London SOUNDWALK location. I felt that Reid’s musical cells had dominated my listening experience in St. Stephen’s Green by blocking out sounds of the surrounding environment and I did not want to feel overly occupied by the mediated content. Thus in Regent’s Park, I tried a different approach to listening. I discarded my headphones and switched to playing the app from my phone’s built-in speakers. Straightway, I realized that my change of approach was effectively adding to the soundscape—perhaps even creating noise pollution—and that the resulting sounds could be heard by other visitors to the park who had no desire to have musical accompaniment to their strolls. I wrestled with that realization throughout my walk, but nevertheless I continued to play the music from my phone to try and gain what I considered to be a better balance between Reid’s cells and sounds that emanated from the park’s environment.

My choice had additional advantages. In Regent’s Park, I was not alone. My husband and son were with me, and playing the SOUNDWALK from my phone allowed them to experience Reid’s work too. SOUNDWALK became more of a group listening activity, as opposed to an exclusionary “Mom-doing-researchon-a-family-outing” activity. At one point, my son, who was three at the time, made the astute observation that the music was changing as we moved; he seemed to understand that Reid’s sounds are tied to place. Playing the music from my phone also allowed me to use my husband’s phone to record both Reid’s musical cells and the sounds of the park. Since Reid’s SOUNDWALK is GPS-enabled, one cannot hear the musical cells outside of the spaces that are geotagged. Albeit far from professional quality, the personal “field recordings” I created on my husband’s phone helped to document the multiple sonic dimensions of my experience so that I could give future students some idea of what I was experiencing.

I did not journal while in Regent’s Park, since I was attempting to make the experience more tolerable for my family, but I do know that playing the music from my phone created a better balance for me. I distinctly recall hearing more natural sounds as a result of changing my approach, including birds, water, and the conversations of other visitors in the park. My recordings also picked up some wind and the occasional crunchy footstep. We also happened to be in Regent’s Park on July 10, 2023, the day that President Biden was scheduled to meet with King Charles III and Rishi Sunak.74 When the President of the United States visits London, he often stays at the residence of the United States Ambassador, which is in Regent’s Park.75 While we were in the park, there was a noticeable police presence and we saw no fewer than four helicopters—some clearly marked as American—that were descending and preparing to land. The sound from the helicopters was so deafening that, in my recordings, it obliterates Reid’s SOUNDWALK.

Although one might contend that the bulk of my experiences of Reid’s SOUNDWALK reflects a binary of embracing technological mediation—in this case, headphones—or not, I would argue that my experiences nevertheless open the door for nuanced observation and discussion, both pedagogically and personally. First, with regard to technology, the decision to play audio directly from a phone instead of through headphones exposes the important issue of alternate modes of listening. How does one choose to use a given technology, and why? Deviating from listening norms also ties into questions concerning the listener’s agency. How closely does one follow an artist’s instructions, and why? Second, considering the circumstances of each listening experience allows for the examination of personal and environmental influences. With whom does one listen? And how does one listen? These are all issues that could be discussed in the classroom, but individual listeners may also benefit from contemplating these questions.

In my experiences of SOUNDWALK, the physicality of my listening shifted from place to place. During my walk in St. Stephen’s Green, which was my first encounter with Reid’s work, I mostly adhered to Reid’s instructions. In Regent’s Park, where I felt more familiar with Reid’s work and intentions, I deviated from her directions, allowing her music to sound from my phone and mingle with the surrounding people, objects, and landscapes. Personal circumstances played a key role in both Regent’s Park and St. Stephen’s Green, since in London I walked with my family and in Dublin I walked alone. Clearly, political events of the day also impacted my soundwalk in Regent’s Park. Reid could not have anticipated President Biden’s visit, nor that it would have prompted me to think more broadly about the park, its visitors, and even its diplomatic history.

Such observations move far beyond the simple presence of technological mediation, thereby complicating its function and impact. They reveal possible tensions between artistic intent and audience intervention. The context of a mediated walk, which can include a host of variables, also accords meaning to the experience. These are issues well worth contemplating to oneself, but they are also well worth presenting to students.

Case Study: Reid’s SOUNDWALK, Student Discussion

I base the second half of my case study on my students’ own observations and narratives. I customarily challenge my students to engage critically with questions pertaining to technological mediation in soundwalking, and they often take our classroom dialogues well beyond binary observations into more meaningful territory. For pedagogues interested in including soundwalking in their teaching, I offer my unit framework immediately below as a point of reference. Explaining how I structure my unit also provides a launchpad to describe my own students’ conversations from fall 2023, which concretely illustrate the nuanced dialogues they have produced. I have included soundwalking in my courses since the fall of 2021, and many of my students have been invigorated by the soundwalking unit I have designed. I incorporate soundwalking most often in my general-education course on music and the environment, which serves underclassmen—primarily freshmen and sophomores—of varying interests and a diversity of majors.76 Over a two-week period, outlined in table 1, my students readily participate in and discuss various soundwalks.

| Day | Topic | Readings and Recordings77 / Assignments |

| 1: Monday | Unmediated Soundwalking | Westerkamp’s “Soundwalking” |

| Westerkamp’s “Soundwalking as an Ecological Practice” | ||

| Explain/Assign: Unmediated Soundwalk | ||

| In-Class Discussion Questions: In what kind of setting would you like to take a soundwalk (e.g., rural, urban, trails, paved walkways)? Why? Is there consensus in your group, or is there [a] diversity of settings? | ||

| 2: Wednesday | Design and Impact of Soundwalks | Carras’s “Soundwalks: An Experiential Path to New Sonic Art,” Parts 1–6 |

| Gutiérrez, Leonardson, and Long’s “How Do Soundwalks Engage Urban Communities in Soundscape Awareness?” | ||

| Gutiérrez’s “What Is a Soundwalk?” (Video) | ||

| In-Class Discussion Questions: What are possible benefits of soundwalking? Could taking a soundwalk draw attention to any broader issues or concerns outside of nature? | ||

| 3: Thursday | TA Session | Planning Your Soundwalk |

| 4: Monday78 | Mediated Soundwalking | Smolicki’s Soundwalking through Time, Space, and Technologies, “Introduction” |

| Vankin’s “Griffith Park Hikers, Listen Up” (Los Angeles Times) | ||

| No In-Class Discussion: Explanation of IRB Study (to be completed the following class period) | ||

| 5: Wednesday | Urban Soundscapes | Westerkamp’s “Soundscape of Cities” |

| Daugherty’s MotorCity Triptych (Musical Recording) | ||

| In-Class Discussion Questions: IRB Study (see below) | ||

| 6: Thursday | TA Session | TBD: Determined by Needs/Interests of Students |

| 7: Friday | N/A | Due: Unmediated Soundwalk Assignment |

In late September of 2023, I asked my students to engage with Reid’s SOUNDWALK.79 Before considering Reid’s work, though, we spent time with Westerkamp’s ideas regarding unmediated soundwalks. My pedagogical purpose for including Reid’s SOUNDWALK was to balance the focus on unmediated sound with at least one extended mediated example, thus providing a comparative soundwalk for students using technology that would be familiar to them. I surmised that students might have a lot to say about a soundwalk that incorporated the modern, ubiquitous tool of headphones.

Since I knew students could not engage directly with Reid’s work at our home institution or its city (the University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida), I assigned to my students a 2021 article by Deborah Vankin about Reid’s Griffith Park walk and invited them to explore Reid’s SOUNDWALK website prior to our fourth class meeting of the unit.80 During class, I presented a summary of my summer experiences with Reid’s SOUNDWALK and supplemented course materials with my personal photographs and sound clips.81 Even though my students could not experience Reid’s work in person, I trusted these various resources could allow students to begin considering the soundwalk’s significance.

During this same class period, I described the IRB study I would conduct during the next (fifth) class period, which would present in-class discussion questions about mediated soundwalking. In that fifth class period, I presented four numbered prompts (below), which consisted primarily of question sets, on a discussion board within Canvas, the online learning platform at the University of Florida. Students were allowed to respond to whichever one of the four prompts they found most appealing, and I gave them the opportunity to chat in small groups before submitting individual discussion posts on Canvas.82 We also followed up in class with a short verbal dialogue.

These are the prompts I posted:

- Has the definition of soundwalk changed over time? Should the definition change over time? Can mediated technology enhance a soundwalk? Degrade a soundwalk?

- How might artists approach the issue of using mediated technology?

- In a mediated soundwalk, should you only walk with your headphones in? Is it acceptable to take them out and play sound through your phone?

- Can you only do something like Reid’s SOUNDWALK by yourself? In what ways could you do this activity with others?

In hindsight, it would have been better to divide the first prompt into two separate sets of questions. This would have allowed one question set to focus on the definition of a soundwalk, while the second set would have targeted the impact of technological mediation on a soundwalk. In future discussions, then, there could be a total of five prompts or I could eliminate the question set regarding the definition of a soundwalk in order to focus more purposefully on technological mediation. I might also change the language of the first set of questions to include “definition and practice of soundwalking” to broaden the discussion. To avoid a potential binary between enhance/degrade, I could condense the second question set to a single question asking, “How does technological mediation affect/change a soundwalk?”

Each question, whether left as phrased or reworded, invokes the concept of value. At the most basic level, the first set of questions about definition targets students’ conceptual understanding and critical thinking; pedagogically, there is merit in simply comprehending a concept. The next issue—the second half of the first prompt—shifts to technology, asking whether it enhances or degrades a soundwalk. This pivot ushers students toward the familiar idea of mediated content; it also requires students to think carefully about how they engage with mediated content. The second prompt, which focuses on artistic methods, prompts students to consider the complexities of the creative process. Artists have many choices to make, and each choice has significance. The third and fourth sets of questions broach the relationship between the volume of sound and its influence on the surrounding environment by asking students not only to evaluate their own listening habits, but also to reflect upon the social impact of their listening. To offer two quick examples, sharing sound can be intentional, as in a group setting where multiple people desire access to the same sound, but there is only one sound source. It can also be unintentional if one simply decides to forego headphones and listen through their device’s speakers without thinking of how this choice impacts nearby people. How one listens can impact more than oneself.

A summary of student responses to the four prompts is provided in table 2. On the day of the discussion, all of my students submitted responses on the Canvas discussion board.83 Students were asked to clearly identify which prompt they were responding to in their submissions; all but four students followed this direction. Yet, the content of these four students’ answers made it clear which prompt they were answering. Since prompts 1, 2, and 3 asked about technological mediation and soundwalking, I will discuss responses only to these three prompts.

| Number of Student Responses | Percentage of Total Responses84 | |

| Prompt 1 | 15 | 22.7% |

| Prompt 2 | 5 | 7.6% |

| Prompt 3 | 37 | 56.1% |

| Prompt 4 | 9 | 13.6% |

Table 2 shows a clear preference for the third prompt, which invited students to consider their own listening habits as well as the auditory impact those habits might have on others. The students’ discussion posts addressing this prompt leaned heavily in two directions. First, several students found it acceptable to play sound through a phone’s speakers on a soundwalk, and they actually encouraged this behavior in order to better interact with both the artist’s constructed sound and the surrounding environment. Second, many students suggested using dual modes of listening during a soundwalk. Sometimes, they focused on having both options available and switching between using headphones and using a phone speaker, in order to allow for a fuller listening experience.85 Other times, students focused on who would be near them during the soundwalk experience. They suggested playing audible sound while alone but using headphones around other people so as not to disturb their sound environment. Only a handful of students were adamant about only using headphones.

Some discussion posts provided more nuanced reflections on the classroom material. One student suggested that using a phone speaker lets the phone act as “more of a guide,” perhaps propelling or pushing the listener through the surrounding environment.86 Another proposed that the perceived duality between natural and recorded sounds allowed for increased complexity during the listening experience.87 Their response implied that artistic and environmental sounds can interweave. Conversely, a different student remarked that highend, noise-canceling headphones could greatly alter a soundwalk.

While listening through headphones, you would mostly be hearing the sounds from the headphones with the sounds of your environment becoming background noise or possibly completely inaudible depending on the level of noise-cancellation in the headphones.88

Advocating for safety, two students also noted that walking with headphones could mute environmental sounds that would otherwise signal danger. Here is one student’s take:

In a mediated soundwalk, I feel as if that you should not only go on soundwalks with just your headphones in. This is because this could potentially make you less aware of your surroundings when walking and could put the person doing the soundwalk in danger of any passing people, bikes, or other potential harms.89

When read back-to-back with the remark about noise cancellation, the concerns about safety become more pressing. It is not hard to imagine getting immersed in recorded sound and letting your attention to safety lapse when using headphones of superb quality. Perhaps in a space constructed expressly for pedestrians, without bicycle or vehicle traffic, soundwalkers’ safety is a bit more protected by virtue of the space’s design. In that situation, as one student observed,

having headphones in . . . allows us to block out the sound from outside of our headphones and just focus on the different aspects of the audio. This would also allow us to take in the visual aspect of our surroundings as there are less distractors.90

This last observation brings the artist’s intention, whether a soundwalker may be aware of it or not, to the foreground. Does an artist intend for soundwalkers to become engrossed with the audio, perhaps paradoxically as a means to focus on the surrounding visual instead of sonic environment? More generally, how much weight does, or should, the artist’s intention have on a soundwalker’s experience? Three students weighed in on this dilemma, with one writing:

Taking off the headphones is a way for the listener to make the soundwalk their own, and individualize it to a point where it can resonate deeper with the person. Although this is not exactly the artists [sic] vision, it is a way to insert yourself into the space and their work.91

This student prioritizes the listener over the artist.92 The artist is not completely disregarded, but it is acceptable for the individual’s experience to supersede the artist’s original intention. In other words, the artist may set parameters, but individual listeners will shape the outcome.

In contrast, another student prioritized the artist over the listener:

I think that both options [listening with or without headphones] are acceptable, but that it depends on the artist’s intention. For example, if the artist wants to have the listener tie together the mediated sound through the headphones with the visual stimulus of the natural world, then the headphones should be used so the listener can understand the parallels or meaning behind the artist’s decision. However, if the artist is not specific about using headphones, then I believe that playing the mediated sound through a speaker could better ground the soundwalk to the natural music and the environment.93

It becomes the artist’s responsibility, then, to clearly communicate how their audience is to engage with their work. Without well-defined instructions, the soundwalker is free to make their own decisions.

A final subset of students proposed alternate ways of listening, moving beyond the two options offered in the prompt. Three students advocated for using a headphone in only one ear.94 Personal-stereo users exhibited this behavior in Bull’s Sounding out the City, as did participants in Sonic Histories.95 Another student suggested wearing headphones around their neck.96 The latter would allow the audio to be “loud enough to hear, but not loud enough to disturb others,” thus directing the sound “towards your ears, away from others, and with enough space to allow natural sounds to reach your ears along with the mediated soundwalk.”97

While the third prompt encouraged students to evaluate their own listening habits, the first prompt focused on general comprehension and the possible benefits of mediated content. Students primarily responded in the affirmative to the first question set, which asked if the definition of “soundwalk” had changed over time. Several students drew on Westerkamp and indicated that her definition needed to change because the world is changing, particularly in light of technological advancements.98 One student argued that Westerkamp’s definition of a soundwalk already allowed for creativity and growth: “The definition of soundwalk (‘a walk with a focus of listening to the environment’) was very broad to begin with and allowed room for interpretation.”99 Another student implied that change was ongoing, and that by expanding what constitutes a soundwalk, soundwalks themselves can become more diverse and inclusive.100 I have not assigned my students any of the earlier writings I cited by Black and Bohlman, Galloway, or Shaw, but these observations lead me to believe that students could engage productively with them.101

Responses to the second question set (of the first prompt), about whether mediated technology enhances or degrades a soundwalk, were more divided. Several students pointed out the positive ways technology adds to soundwalks. One student cited increased accessibility for the participant, noting that “someone who is hard of hearing can still participate in a soundwalk if they have a cochlear implant or hearing aids.”102 Another student noted modern reliance on technology, particularly by Generation Z.103 They proposed, “with younger generations being more dependent on technology, incorporating technology into soundwalking could make it more accessible and engaging for younger generations, which will keep the practice of soundwalking alive.”104 Echoing Westerkamp’s description of the capabilities of audio technology in Kits Beach Soundwalk, a third student noted the potential for recognizing overlooked sounds by “utilizing microphones to amplify the quieter noises that typically get drowned out by more prominent ones” but treaded into perhaps more controversial grounds by describing the use of “audio technology to minimize or completely eliminate the dominant sounds.”105 Referring directly to Westerkamp’s work, another student recollected that “Westerkamp herself used technology to record and share soundwalks through her radio show.”106 This student also used newly acquired course knowledge to argue that “the concept of unmediated listening has always been more of an ideal and the complete exclusion of technology was never intended.”107 Yet another student hypothesized that soundwalking will remain

an ever-evolving activity with the emergence of new and future technologies. . . . With the advent of new and emerging technologies, including digital recordings, on-demand audio streaming, virtual reality, and artificial intelligence, individuals will discover news ways [to] engage in a soundwalk and thus expand the frontier of the forms and mediums that can add and layer to the core activity of a soundwalk.108

A few students, though, were hard pressed to find advantages to mediated soundwalks. One simply stated at the end of their post, “the only thing that should be listened to on a soundwalk is the environment in the immediate area of the person conducting the soundwalk.”109 Another student suggested that technological mediation can distract a listener, but situated that claim within the observation that others’ technology may be a part of the soundwalking environment.

Mediated technology degrades a soundwalk because it interferes with your environment and is distracting. Your environment should be everything around you, even if its [sic] from other people’s technology. But when you use technology, it distracts you from perceiving everything around you.110

Subjectivity was another theme that ran through the students’ discussion posts. A person’s individual experiences, needs, and preferences will undoubtedly come into play as they choose what kind of soundwalk to undertake, or even whether to take a soundwalk at all. An intriguing angle that I did not even conceive of involved the idea of escape. One particularly creative student offered the following commentary:

I find a lot of intrigue in thinking about how that same [mediated] technology could . . . provide us with an escape if we so choose. What makes us want to remove ourselves from a place is just as much a part of it as what makes us want to embrace it and be a part of it. We should not ignore this. At the beginning of this class, we talked a lot about how active listening is one of the keys to doing a soundwalk, but what if my environment makes me not want to listen? Technology could give us a way to do that.111

This student rightly asserts that the opposite of an expected or frequent reaction can occur. We spend significant time in my general-education course talking about how to listen and become an active participant in an environment. We focus on primarily positive interactions and experiences. Yet, some of us may find an environment repulsive; a person may reject engaging further with it or in it. To ignore that someone may feel negatively about an environment, and by extension disregard the reality that technology can draw us out of that space, is tantamount to disregarding the environment and its impact.

This notion of welcome distraction recalls Bull’s observation that listening to a personal stereo could provide a sense of escapism. To describe one participant’s experience, he explains that

[u]nwanted thoughts are blocked out during her journeying till she arrives at her destination where her attention is taken up with other things. In this instance the personal stereo functions as a kind of “in-between,” filling up time and space in between contact with others, transporting the user out of place and time into a form of weightlessness of the present.112

Although my student’s response has more of a negative tone, it is clear, once again, that their observation parallels earlier listening behaviors.

Students engaged least with the second prompt, but their responses still provided revealing commentary pertaining to it. This prompt aimed to put students in the mindset of the creative artist. A handful of students focused primarily on the importance of eschewing technological mediation in order to center natural sounds, a stance that may reveal a bias in my own teaching. As mentioned earlier, I draw on Westerkamp at the beginning of the soundwalking unit and require an unmediated walk for the course’s soundwalking assignment. A couple of students latched onto the idea of control, with one even suggesting that an artist could have complete control over a soundwalk if they use virtual reality.113 Another acknowledged that while mediated technology can point the ears to potentially overlooked sounds, technological mediation will always insert the artist into the listening experience by influencing what is heard:

[For] an artist who wants listeners to pay attention to specific sounds and is trying to make quieter sounds become more recognized, a mediated soundwalk will probably allow them to achieve this goal. . . . However, for an artist who wants the listener to interpret the sounds on their own and reflect on what they believe the soundwalk represents for them, mediated technology will only hinder that natural response from the listener. To mediate is to involve oneself in something which means a soundwalk with mediation will inherently evoke a response that is influenced by the artist.114

By and large, I was impressed by my students’ responses. Many of them offered earnest and meaningful reflections that went well beyond any simple binary division, which suggests that they wanted to engage with and found value in the discussion. In some cases, I would have liked to have seen less affirmation from my students about the issues I presented in class.115 Yet, it seems important to note that students in my general-education course are largely freshmen and sophomores, and many of these undergraduates are in the process of learning how to think critically and express their thoughts.116 But as evidenced by several of the quotes presented in this analysis, many students are ready to jump into nuanced classroom discussions. Those who choose not to participate verbally in the classroom can still benefit from having a space where they see and hear their peers modeling critical-thinking skills.

I would take one more step and assert that while I am arguing that mediated soundwalking can be examined and debated in detail in an undergraduate university course, and that this activity has value, my students’ answers to my questions are not the most valuable aspect of classroom discussion. The dialogues that result from their active engagement with the questions have the greatest significance. In other words, I am not seeking any particular answers to the questions I ask. My goal is for students to be able to demonstrate that they can engage with questions and respond thoughtfully to them, and I am grateful to witness many of them rising to that challenge. In fact, students are pushing me, too.117 In having conversations with Generation-Z students about mediated soundwalks, I have become more aware of not just their embrace of multiple technologies, but how they consider the impact of those technologies on their daily lives. It is heartening to know that these students are well equipped to contemplate how various technologies have an effect on surrounding environments.

Revisiting Our Route

As revealed in their nuanced observations regarding technological mediation in soundwalks, my undergraduate students are broadening their understanding of soundwalking. They recognize that technological mediation is far more complex than a simple presence-or-absence binary construction and, once noted, can apply critical thinking to assess the benefits and detriments that arise in a soundwalk. In fact, members of Generation Z may find mediated soundwalks attractive precisely because of their technological mediation. And yet, despite the possibilities technology affords for future soundwalks, particularly in the realms of streaming and virtual reality, there will always be soundwalkers who prefer to engage only with an unmediated natural environment.

In wrestling with questions of sonic impact, listener etiquette, personal safety, artistic intention, and other such issues regarding the use of technology in soundwalking, my students and I acknowledge that there is much complexity in the experience. We refute any assertion that there is a single, “correct” way to incorporate technological mediation, let alone a “right” way to undertake a soundwalk. Our grappling with a multitude of interconnected topics aligns with Black and Bohlman’s contention that open conversations about difference, diversity, and privilege in soundwalking can be far more valuable than simply taking a soundwalk to practice “better” or more attentive listening.118 Our grappling also provides a response to Smolicki’s advocacy for soundwalking as a critical practice. We are not developing any definitive answers or solutions to the questions we raise; rather, we are noticeably moving beyond “innocent” conversations. We are thinking critically.

My students remain interested and invested in soundwalking, and as such, they eagerly consider what soundwalking means for all of us. Buoyed by my students’ engagement with this exercise, I invite instructors to move beyond the “canonic exercise” of a “simple” soundwalk and try soundwalking with headphones.

- 1↩

- Jacek Smolicki, “Composing, Recomposing, and Decomposing with Soundscapes,” in Soundwalking through Time, Space, and Technologies, ed. Jacek Smolicki (Routledge, 2023), 182.↩

- In a summary for a 2024 study titled “Exploring Technology Preferences Among Gen Z,” the Consumer Technology Association reported that Gen Z owns, on average, thirteen technology products—for example, smartphones, wireless earbuds/headphones, gaming consoles, and televisions. Gen Z reports using six of these products on a daily basis. Smartphones, and in particular Apple iOS smartphones, are their preferred device, with just under 95% of Gen Z owning one. See Consumer Technology Association, “CTA Research: Exploring Gen Z Views and Preferences in Technology,” February 20, 2024, https://www.cta.tech/press-releases/cta-research-exploring-gen-z-views-and-preferences-in-technology.↩

- In this article, I often shorten “technologically mediated” to simply “mediated” to keep the text from becoming cumbersome. All references to mediated soundwalks or mediated soundwalking in this article are referring to technological mediation, as opposed to other kinds of mediation. Similarly, unmediated soundwalks or soundwalking refers to the absence of technological mediation.↩

- Other mediated soundwalks with easily accessible online audio components could also work as points of departure for student discussion, including Saltwater Soundwalk, Sonia Killmann and Laura Fisher’s “Going Out|Going In,” John Luther Adams’s Soundwalk 9:09, or the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Kids Soundwalks.↩

- Amanda M. Black and Andrea F. Bohlman, “Resounding the Campus: Pedagogy, Race, and the Environment,” this Journal 8, no. 1 (2017): 6.↩

- Black and Bohlman, 6. See also Tyler Kinnear et al., “Sonic Histories: Reckoning with Race through Campus Soundscapes,” Environment, Space, Place 15, no. 1 (2023): 37. In the article’s tenth footnote, the authors provide a trove of resources for soundwalking in connection to cultural ethnography, geography, urban planning, education, and sonic art.↩

- Black and Bohlman, “Resounding the Campus,” 16.↩

- Black and Bohlman, 6.↩

- Black and Bohlman, 15.↩

- Black and Bohlman, 7.↩

- Black and Bohlman, 18. Beyond the Belltower grew out of a 2015 soundwalk that Bohlman organized for her undergraduate students through the UNC-Chapel Hill campus. On this walk, they all passed a Confederate statue where a demonstration was occurring. Bohlman became concerned about student safety and the possibility of making an unintended political statement, ultimately concluding that she had not adequately prepared for the soundwalk. In response to this experience, Bohlman’s graduate students developed a soundwalk, Beyond the Belltower, in a seminar setting, which, in addition to the aforementioned nine scores, included a digital soundmap and a display of primary source materials at the UNC-Chapel Hill music library. A new set of Bohlman’s undergraduate students experienced Beyond the Belltower in the context of a music and politics course, and the experience was consciously situated “within the legacy of radical black performance rather than the Canadian soundscape school, which has largely avoided connecting sound with the politics of race and was shaped exclusively by white composers of European heritage.” Black and Bohlman, 24.↩

- Black and Bohlman, 19. Black and Bohlman’s article mentions the “Black and Blue Tour,” which includes sites historically connected to slavery, racism, and activism. It has recently been updated and can be found at “The Black and Carolina Blue Tour,” UNC University Libraries, accessed April 19, 2024, https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/b84110ce4a204e779e6915e5786ffbe4.↩

- Black and Bohlman, 9.↩

- Black and Bohlman.↩

- Black and Bohlman, 17.↩

- Kinnear et al., “Sonic Histories,” 34. The authors describe the triumphant narrative as such: “The narrative often goes like this: that historical discrimination against racial minorities is a sad fact, but the university to which you belong has been consistently progressive relative to others at the time. These messages tend to be positive and uplifting—that while there is still work to do, we have always risen to the challenge. This triumphant narrative underestimates the oppression of racial minorities that occurred in the past and present.” See Kinnear et al., 41.↩

- Kinnear et al., 35.↩

- Kinnear et al.↩

- Kinnear et al., 38.↩

- Kate Galloway, “Making and Learning with Environmental Sound: Maker Culture, Ecomusicology, and the Digital Humanities in Music History Pedagogy,” this Journal 8, no. 1 (2017): 51.↩

- Galloway, 56. The courses are titled “Music, Sound, and the Environment in the Anthropocene” and “Music, Technology, and Critical Geography.” Galloway also notes that soundwalk development is not always a straightforward practice. Ideally, students learn to value the creative process, which may include several revisions. See Galloway, 54.↩

- Galloway, 55.↩

- Galloway, 54.↩

- Hildegard Westerkamp, “Soundwalking as Ecological Practice,” Inside the Soundscape, November 3, 2006, last modified 2023, https://hildegardwesterkamp.ca/writings/writings-by/?post_id=14&title=%E2%80%8Bsoundwalking-as-ecological-practice—2023-update:-spanish-translations-published—2-publicaciones-en-espanol.↩

- For Westerkamp’s own description of her radio work, see “The Soundscape on Radio,” in Radio Rethink: Art, Sound and Transmission, ed. Daina Augaitis and Dan Lander (Banff Centre for the Arts, 1994), 86–94. See also Smolicki, Soundwalking through Time, 3; and Westerkamp, “Soundwork,” Inside the Soundscape, accessed May 30, 2025, https://www.hildegardwesterkamp.ca/sound/.↩

- R. Murray Schafer arrived at Simon Fraser University (SFU) in 1965, the same year the university was founded, and five years prior to the formal conception of the WSP in 1970. He began working on music and soundscape education, publishing Ear Cleaning, a “volume of lecture notes related to his approaches to teaching first-year university music students,” in 1967. Michael Palmese, “The World Ear Project (1970–87): Soundscapes, Politics, and the Genesis of Acoustic Ecology,” Resonance: The Journal of Sound and Culture 3, no. 1 (2022): 70. See also Milena Droumeva and Randolph Jordan, eds., Sound, Media, Ecology (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), vii. The introductory section to Sound, Media, Ecology provides a succinct timeline of Schafer’s work with the WSP, along with the work of other WSP members.↩

- Kinnear et al., “Sonic Histories,” 37. WSP member Barry Truax shares similar information: “Besides the recordings, the WSP team established ‘soundwalking’ as a simple technique to evaluate the perceptual and qualitative aspects of a soundscape through a listening walk.” See Truax, “Acoustic Ecology and the World Soundscape Project,” in Sound, Media, Ecology, ed. Milena Droumeva and Randolph Jordan (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 23.↩

- See Droumeva and Jordan, Sound, Media, Ecology, viii. Broomfield, Huse, and Davis continued recording around Vancouver until 1976, but most recordings were made during their first year of work.↩

- Droumeva and Jordan, ix. Truax claims that “from the perspective of acoustic ecology, the most important research of the WSP was their initial study of The Vancouver Soundscape.”↩

- See Droumeva and Jordan, Sound, Media, Ecology, ix–x; and Truax, “Acoustic Ecology,” 26. Mitchell Akiyama suggests that Soundscapes of Canada is more significant than The Vancouver Soundscape, as Soundscapes of Canada “articulated the group’s ambitious goal of restoring the integrity of the nation’s sonic environment.” Akiyama, “Nothing Connects Us but Imagined Sound,” in Sound, Media, Ecology, ed. Milena Droumeva and Randolph Jordan (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 117.↩

- Droumeva and Jordan, Sound, Media, Ecology, xi.↩

- For example, Akiyama has addressed the WSP’s omission of First Nations perspectives in Soundscapes of Canada both in public-facing forums and in his scholarly writing. His research clearly shows that the radio program ignored First Nations and other minorities, effectively excluding sounds from these populations and generating a Eurocentric bias. See Mitchell Akiyama, “Unsettling the World Soundscape Project: Soundscapes of Canada and the Politics of Self-Recognition,” Sounding Out! August 20, 2015, https://soundstudiesblog.com/2015/08/20/unsettling-the-world-soundscape-project-soundscapes-of-canada-and-the-politics-of-selfrecognition/. See also Mack Hagood, “R. Murray Schafer Pt. 2: Critiques & Contradictions,” Phantom Power, podcast, October 29, 2021, https://phantompod.org/ep-30-r-murray-schaferpt-2-critiques-and-contradictions/; and Akiyama, “Nothing Connects Us.”↩

- Mack Hagood writes about an intriguing project undertaken by Alan Teibel in the late 1960s and early 1970s titled environments. These records, released as pairs, sonically conjured spaces such as the beach or a forest through carefully manipulated field recordings. The purpose of environments, though, was more therapeutic. Listeners were not supposed to devote attention to the recordings; rather, “the proper experience of these records involved not listening to them at all.” Teibel argued that “only irregular, aperiodic noise would suffice as a technology of the self, calming the distracted mind and letting the user perfect her state of consciousness, because its lack of pattern supplied nothing for the mind to grasp onto.” Hagood, “The Ultimate Seashore: Environments and the Nature of Technology,” in Hush: Media and Sonic Self-Control (Duke University Press, 2019), 118, 119. Thus there are environmental and technological connections between soundwalking and environments, but the purpose is vastly different.↩

- Palmese, 60.↩

- Palmese, 65.↩

- Palmese.↩

- Janet Cardiff, The Walk Book (Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, 2005). Cardiff created her first audio walk during a residency at the Banff Centre in 1991, then proceeded to create several audio walks in New York and London in the 1990s and early 2000s. See Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller, “Walks: Explanation,” accessed May 20, 2025, https://cardiffmiller.com/walks/. Ruth Bretherick notes that Cardiff stopped creating audio walks in 2006 and switched her focus to video walks in 2012. See Bretherick’s “The Urge to Disappear: Janet↩

- The book, itself, is one of the most visually arresting books I have seen on any subject. It includes full-color maps, annotated scripts, and photographs, as well as judiciously considered changes in font color, size, and style. For example, Cardiff’s words are in blue font. Important text or phrases are in bold typeface and key people and titles are highlighted in yellow. There are several superscript comments added to the main text, which function like an extra voice—like someone adding asides over your shoulder—as you are reading. These superscript comments are different from the footnotes, which appear in wide margins to the side of the main text, allowing readers to see references immediately next to the relevant text as opposed to underneath it.↩

- Cardiff and Miller, “Walks.”↩

- Cardiff, The Walk Book, 25 (bold in original).↩

- Some of the audio insertions are musical in nature, such as church bells, a chanted nursery rhyme, or a brief instrumental excerpt. Although I have not listened to every walk, it is clear that composed underscoring is not typical.↩

- Bretherick, “Urge to Disappear,” 429.↩

- Tim Shaw, “Paths of Dependence: Welcoming the Unwelcome,” in Soundwalking through Time, Space, and Technologies, ed. Jacek Smolicki (Routledge, 2023), 116.↩

- Shaw, 131.↩

- Matthew Burtner, “EcoSono: Adventures in Interactive Ecoacoustics in the World,” Organised Sound 16, no. 3 (December 2011): 236. For Smolicki’s incorporation of Burtner’s work, see the above-cited Smolicki, “Composing, Recomposing, and Decomposing,” 184.↩

- Burtner, “EcoSono,” 236.↩

- Shaw, “Paths of Dependence,” 131. Shaw cites insertions of two particular kinds of sound that can fictionalize a surrounding environment: studio-produced Foley audio and/or text-based storytelling.↩

- Smolicki, Soundwalking through Time, 6.↩

- Smolicki.↩

- Galloway, “Making and Learning,” 54.↩

- “Hildegard Westerkamp—Kits Beach Soundwalk (1989),” uploaded by Boundless YouTube account, December 4, 2015, 10 min., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hg96nU6ltLk. Westerkamp acknowledges that a sound editor can augment an original recording: “I could shock you or fool you by saying that the soundscape is this loud [volume level of audio increases], but it is more like this [volume level of audio decreases]” (00:1:42–00:02:01) and “we have bandpass filters and equalizers. We can just go into the studio and get rid of the city [sound]—pretend it’s not there” (00:03:03–00:03:15). She does not offer critique after making these statements, but she certainly opens up space for critique.↩

- See “About,” Ellen Reid’s personal website, accessed May 30, 2025, https://ellenreidmusic.com/about.↩

- Jeff Lunden, “Central Park Is Alive with the Sound of Music, Thanks to a SiteSpecific App,” Deceptive Cadence, NPR, October 24, 2020, https://www.npr.org/sections/deceptivecadence/2020/10/24/927121609/ellen-reid-soundwalk-central-park-gps-location↩

- “Ellen Reid SOUNDWALK,” accessed May 16, 2024, https://www.ellenreidsoundwalk.com/ (italics original).↩

- First, I have to thank Leo Walker for drawing my attention to the SOUNDWALK in St. Stephen’s Green. I would not have known about it without our conversation! Second, when I encountered the work, SOUNDWALK was offered in nine cities around the world: Athens, Dublin, London, Knoxville, Laguna Beach, Los Angeles, New York City, San Francisco, and Tokyo. See “Find a Soundwalk,” Ellen Reid SOUNDWALK website, accessed May 16, 2024, https://www.ellenreidsoundwalk.com/locations-1. Two walks were available in Los Angeles: one on the UCLA campus and one in Griffith Park. Reid had also developed past soundwalks in Norfolk, Vienna, and Virginia Beach, Virginia; Jacksonville, Oregon; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and Saratoga Springs, New York.↩