Acrucial step toward reshaping an intellectual field is understanding its structures and the stories that those structures tell. This essay discusses a pedagogical approach, which we employed in two classes, for exploring physical designs and conceptual paradigms that are used to organize both large- and small-scale collections of sound recordings of Black music, and for articulating the narrative assumptions entailed by processes of selecting, organizing, and presenting sound collections. After exploring the ways that these processes create stories, we encouraged students to imagine the possibilities of new structures and stories, laying the groundwork for producing historical methodologies that have the potential to upend, add to, or create alternatives to existing narratives.A crucial step toward reshaping an intellectual field is understanding its structures and the stories that those structures tell. This essay discusses a pedagogical approach, which we employed in two classes, for exploring physical designs and conceptual paradigms that are used to organize both large- and small-scale collections of sound recordings of Black music, and for articulating the narrative assumptions entailed by processes of selecting, organizing, and presenting sound collections. After exploring the ways that these processes create stories, we encouraged students to imagine the possibilities of new structures and stories, laying the groundwork for producing historical methodologies that have the potential to upend, add to, or create alternatives to existing narratives.

In service of this project, we collaboratively facilitated two of three iterations of a course that Sophie designed and alternatively called “Collections and Colonialism” and “Scraps of the Archive: Race, Theory, Performance.” One essential argument of both courses was that collection design and description are not neutral, butideological. This argument animated our analysis of the design decisions that make up physical and digital Black music anthologies, as well as design decisions that shape a given digital repository’s display interface. Each such decision communicates information about how archivists, curators, web designers, digital project teams, and other institutional stakeholders want the user to understand those collection materials.1 1

In class discussions throughout each semester, we brought related work by archival scholars and practitioners into discussion with the organization and display of a variety of digital and physical archives and collections that construct often communal and intimate Black (and Indigenous) spaces and histories. By analyzing the form as well as the content of these collections, we were able to recognize the meanings that have been produced through an array of collections’ visual strategies, information displays, and navigational decisions; to identify where systems of power have an effect on these curatorial choices; and to imagine what meanings could be produced had the choices been different. In a fall 2020 iteration of the “Collections and Colonialism” seminar specifically, we focused our efforts on examining the structure and organization of music collections and anthologies through these archival contexts.

Given that our work is informed by scholarship for which it is important to acknowledge the shifting locations of power, we want to articulate our own intellectual and professional positions and describe the context through which our methods took shape.

Our collaboration during Sophie’s two-year appointment (August 2020–22) was remote. Both Sophie and Laura were working at Brown University. Sophie was hired as an American Council of Learned Societies Emerging Voices Fellow to work in the Center for Digital Scholarship at Brown University Library and to teach in the University’s Department of American Studies and the Public Humanities program. Laura is a musicologist who holds an appointment at Brown as Performing Arts Librarian, a significant part of which is directing the Orwig Music Library.

In part because Sophie inhabited a position at the intersection of multiple divisions of the Brown University Library2 and the interdisciplinary American Studies department and Public Humanities program, her courses were populated by students from a variety of disciplines including Africana studies, American studies, comparative literature, music, Native and Indigenous studies, public humanities, history, and environmental studies. Fifteen to twenty-one upper-level undergraduate and graduate students registered in each seminar.3 With these classroom sizes and various levels of experience, Sophie was able to prioritize building remote and in-person classroom communities and growing connections with and among her students. For students to enroll, previous experience with research or library work was neither required nor necessary. To our minds, any upper-level seminar-sized classroom in a university with access to digital or physical collections of Black music (including commercial releases) can adapt and apply the pedagogical strategies we outline herein.

As a cisgendered white woman, Sophie considers herself to be a student of the world-building disciplines of Black studies, Native and Indigenous studies, American studies, literary criticism, popular music studies, and archival theory; she cultivates and supports flipped classrooms, uses trauma-informed pedagogy, and reads the scholarship that she teaches with focus and care. Also a cisgendered white woman, Laura takes seriously the call to “do the work” of comprehending and exposing structural bias and racism; exploring the structure of individual collections of Black music in the classes struck her as an opportunity to reach a deeper understanding and to create an opportunity for students to examine source materials with a new and constructive critical eye. Her experience in contingent teaching positions in musicology, including at Brown and at Indiana University, gives her a deep grounding in the relationship between collections and the classroom.

In this article, we bring our goals and experiences together as two intertwining threads. We focus on the cultural history and visual design of collections and anthologies of early twentieth-century Black music and on our approaches to teaching it in the context of Sophie’s courses about histories, theories, and uses of collections and collecting. We have chosen to represent our collaboration here in the format of a dialogue because we feel that the strength of our partnership rests in the ways that not all of our perspectives and methods are shared. Our collaboration worked because we did not attempt to meld our methodologies. Instead, we communicated our goals and methods to one another, brainstormed together, and led different class sessions within the same course. We did not want to lose the frisson of this way of working together by reproducing our different experiences through a singular voice. We also believe that our experiences shape our goals and practices. In using the dialogue format, we aim to show how a deep and sustained relationship between the library and classroom as well as between scholars with complementary but differing backgrounds can result in a rigorous, imaginative, and multimodal entryway to analysis and creation in the context of archives, collections, and anthologies.

Laura begins the article by drawing together recent criticism on the collecting of Black music with some of the existing textbook models for teaching this repertoire. After establishing a foundation in the literature of the field, Laura then passes the text to Sophie, who describes the courses on which we collaborated: the scope of texts and digital and physical archives that we accessed, our modes of accessing the texts and questions of each class, Sophie’s mode of analyzing digital design, and the design of the courses’ final project. Sophie also shares student work in response to the final project prompt. We hope that presenting debates and methodologies within the field as well as our methods of reading and analyzing texts and collections will both provide the reader with frames through which to receive and analyze our teaching and help scaffold for future course/class designs.

In order to illustrate our pedagogy and goals for these collections, Laura then presents three case studies for analyzing a variety of historical anthologies of Black music, which she brought to individual sessions of the courses. First, she focuses onThe Rise & Fall of Paramount Recordscollection, which presents the titular label’s catalog on two thumb drives stored at the center of two collectible suitcases packed with ephemera. Next, she describes how she frames a comparative analysis of the CD compilationsGoodbye, BabylonandGood News: 100 Gospel Greats. She concludes by detailing how she teaches the design and various meanings of online repositories of Black music by focusing on the Library of Congress’s vast National Jukebox archive. In the conclusion, we reflect briefly on our collaboration, highlighting goals and outcomes that proved achievable through our shared and diverging methodologies and meditating on the significance of this work for enabling systematic change.The Rise & Fall of Paramount Records collection, which presents the titular label’s catalog on two thumb drives stored at the center of two collectible suitcases packed with ephemera. Next, she describes how she frames a comparative analysis of the CD compilations Goodbye, Babylon and Good News: 100 Gospel Greats. She concludes by detailing how she teaches the design and various meanings of online repositories of Black music by focusing on the Library of Congress’s vast National Jukebox archive. In the conclusion, we reflect briefly on our collaboration, highlighting goals and outcomes that proved achievable through our shared and diverging methodologies and meditating on the significance of this work for enabling systematic change.

Historiography and Collections of Black Music

Laura: There are two major intellectual strands that were part of my engagement with this topic. The first strand considers the interaction between the organization and presentation of archives and collections and the writing of historical narratives. The second engages with recent scholarship about the history of collections and the collecting of Black music.4 In alignment with these strands, I approached Sophie’s courses by thinking about archives and collections in the broadest possible terms, in terms of size (both “minute” and “monumental”), origin, and the ways collections might depart from typical archival structures to encompass commercially produced and nontraditional forms.5 The music collections at Brown—both their content and their organization—reflect the history of the disciplines they support as well as the systems and standards of collection and organization found in, respectively, American research institutions and the commercial music industry. Compilations and anthologies that are held in the music collections across major research institutions, and in any individual music library’s collections, reveal perspectives about how music scholarship has understood itself and been understood by its supporters; the content and presentation of such collections are underpinned by the modes of thought that informed their creation. The collections of Black music we considered consist primarily of sound recordings; in this type of collecting, amateur and corporate enterprises—the latter with pecuniary goals—have played a predominant role. The background of these collections in both the commercial and the enthusiast worlds makes it all the more urgent to teach students to recognize the aspects of both packaging and curation that take place before and after a collection ends up in the library, and how that packaging and curation furnish a tacit narrative of the contents therein.

Both Marybeth Hamilton and, more recently, Daphne A. Brooks have argued that the collecting and anthologizing of Black music have often been driven by the personal, social, and even political agendas of its (usually white) collectors.6 As Hamilton notes, these agendas did not typically align with the lived experiences of contemporaneous Black people, which indicates that the resulting collections are, at best, incomplete and biased sources of information about Black music, both in general and in the context of specific genres.7 (I note here that genre in popular music itself has a troubled relationship with racial history.) Brooks clarifies that the processes of assembling these collections have drawn on subjective, contingent criteria that exclude the perspectives of the music creators and many of the original collectors.8 Yet such collections continue to play a significant role in shaping an understanding of the history of Black music. Collections of sound recordings create discourse; as Will Straw notes, “record collections are carriers of the information whose arrangement and interpretation is part of the broader discourse about popular music. In a circular process, record collections . . . provide the raw materials around which the rituals of homosocial interaction take shape.”9 While Straw writes about private9 record collections (and homosociality), we here are considering materials held in institutional collections on a variety of scales and used for educational purposes. While some anthologizers have created alternative narratives of Black music through collecting and interpreting against the grain of hegemonic structures, in general there are a few recurring frameworks in place in both educational and commercial settings—spheres that collide head on in the space of institutional music-library collections, where it is common for commercially created recordings to be collected, arranged, and used for pedagogical purposes.10 10

To understand the benefits and limitations of existing organizational frameworks for the study of Black music, we might look to some of the touchstone texts for studying Black music.11 James Haskins’s 11Black Music in America, for example, is narrated according to a series of biographical studies of prominent individuals; this structure aligns with the “genius” narrative of music history, which has been subject to scrutiny and criticism but still finds traction in much recent music-historical work.12 The “genius” paradigm, by focusing on only a small number of individual, phenomenally successful music creators, highlights outstanding (Black) musical achievement but does not lend itself to a contextually rich history, nor does it explore the processes by and structures through which a particular historical narrative came into existence. Another common framework is one oriented around genres as discrete entities, as evidenced in Mellonee Burnim and Portia Maultsby’s excellent 12African American Music: An Introduction.13 This structure allows for a richer context, although it compartmentalizes genres that have deep relationships with one another—and (as alluded to above) some scholars have called for the critical reevaluation of the concept of racialized genres in popular music to begin with.14 A framework perhaps reflected more frequently in sound recording collections than texts is what I call the “corporate history” framework, one that foregrounds the stories of the commercial entities that recorded, produced, and distributed Black music.15 Each of these frameworks demonstrates a valid mode of narrating history, and some have advantages given their ease of comprehension and affirmation of the very existence of Black musical achievement. But each is, at best, an incomplete reflection of the context from which this music arose.

Perhaps one of the best models for the rich historical engagement we encourage our students to aim for is Samuel Floyd’s work.16 Floyd directly addresses the problem of gaps in the sources for a full history of African American music; a clear next step, jumping off from his work, is to consider the organization and structure of collections of sources that do exist.17 In addition, study centered on sound recordings has the advantage of pointing students in the direction of performers as a central aspect of a more fully developed context for music; such a move serves as a corrective to what Daniel Barolsky has identified as the “absence” or “superficial” and thus “marginalizing” inclusion of performers in music-historical study, which has had a particularly pronounced impact on the historical understanding of music creators who are women, people of color, or both.18

Teaching Using Digital and Analog Archives and Collections of Black History

Sophie:By emphasizing the imperative to work with and against the grain of the material structures of collections and sources, and to hear silence as information, Laura beautifully articulates the focus of a course I alternatively called “Collections and Colonialism” and “Scraps of the Archive: Race, Theory, Performance.” Both versions of the course used the lenses of Black studies and Native and Indigenous studies to critically consider the ways that different places and identities have been constructed through the practice of collecting and, conversely, the ways that collections rely on specific conceptions of identity to propose historical narratives. While I created “Collections and Colonialism” as a seminar for upper-level American studies majors and graduate students, I narrowed the scope of “Scraps of the Archive” for an introductory summer-term seminar and focused specifically on Black studies texts and collections. The questions and methods that I describe below are adaptable for both undergraduate and graduate students, in-person and remote contexts, and a range of course durations.Sophie: By emphasizing the imperative to work with and against the grain of the material structures of collections and sources, and to hear silence as information, Laura beautifully articulates the focus of a course I alternatively called “Collections and Colonialism” and “Scraps of the Archive: Race, Theory, Performance.” Both versions of the course used the lenses of Black studies and Native and Indigenous studies to critically consider the ways that different places and identities have been constructed through the practice of collecting and, conversely, the ways that collections rely on specific conceptions of identity to propose historical narratives. While I created “Collections and Colonialism” as a seminar for upper-level American studies majors and graduate students, I narrowed the scope of “Scraps of the Archive” for an introductory summer-term seminar and focused specifically on Black studies texts and collections. The questions and methods that I describe below are adaptable for both undergraduate and graduate students, in-person and remote contexts, and a range of course durations.

In order to think throughcollection as a mode of public representation and history making, students in each course studied writing from a variety of disciplines as well as from physical academic and digital public archives. In “Collections and Colonialism,” where I first began my collaboration with Laura, students learned about the practices and stakes of archival description, display, and research from Black studies theorists like Saidiya Hartman and Christina Sharpe and Indigenous studies scholars such as Margaret Kovach and Lisa Brooks. At the same time, students grappled with the living histories of racism and colonial extraction as well as the theoretical and practical possibilities and affordances of the archival field from digital-humanities practitioners like Marisa Elena Duarte and Kim Gallon and archivists such as Jessica Tai and Jarret M. Drake.19

We approached these texts in two ways. First, we parsed their ideas through close reading, focusing on the ways that each author discusses the history, creation, design, use, and analysis of archives and collections. Second, I asked students to apply their knowledge of those same essays in order to analyze various digital and physical archives and collections. To guide students in their analysis of the design of online collections and repositories, it is helpful to introduce them to the unique features and affordances of digital platforms. I met this challenge by producing a document in collaboration with Elli Mylonas, then the Senior Digital Humanities Librarian at the Brown University Library, called “Approaching Site Models,” which gave students a toolkit for noticing the ways that archival, web, and production design can amplify and contest the meanings of the collection itself.20 By engaging with multidisciplinary texts spanning history, theory, poetry, and fiction as well as archival resource records, collection descriptions, and finding aids in conversation with visual digital archival design, students were able to think critically and constructively about the histories, afterlives, and contemporary practices of creating and using archives and collections in digital and physical contexts. 20

InSilencing the Past, Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s meditation on the ways that power suffuses the production of history, Trouillot describes the construction and codification of narrative silence: first, in the act of creating sources, and second, in their assembly. According to Trouillot, it is the second process of assembly that generates the historical archive. He writes,

The making of archives involves a number of selective operations: selection of producers, selection of evidence, selection of themes, selection of procedures—which means, at best the differential ranking and, at worst, the exclusion of some producers, some evidence, some themes, some procedures.21

Trouillot’s text was my seminar’s opening salvo. Throughout each semester, we critiqued these “selective operations” in dialogue with the work of other critics, researchers, and practitioners. Specifically, what Trouillot calls the “active act of production”—whereby historical actors actively (if not consciously) select the stories that will populate the historical record—became a primary site of analysis for my students.22 In class, we assessed and read considerations of the ways that archives and collections have been aggregated, purchased, cataloged, processed, and preserved. Influenced by the extensive work of archivists who have argued against the idea that neutrality is an achievable or even desirable goal for archival description,23 I chose not to assign heavily from the breadth of archives, collections, and texts that hegemonically produce racism and white supremacy. Instead, my seminars focused on readings and repositories that enable students to both critique and build on conversations that work against and in defiance of those materials.24 “Collections and Colonialism” became a place where students could join contemporary conversations about archives and imagine how archives could be constructed to produce history anew.

One particularly generative lesson in the spring of 2022 involved putting two defiant, nontraditional archives into conversation: Matthew M. Delmont’sBlack Quotidian: Everyday History in African-American Newspapers and Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley’s Black Trans Archive.25 While both Delmont and Brathwaite-Shirley use digital pathways and design in their creative digital archives to produce the kind of access that emphasizes archival gaps and silences and creates a sense of community and accountability, their use of sources and priorities are quite different. Students noticed that, by choosing to focus on Black newspapers to communicate that everyday Black life is an essential form of Black history, and by making its multiple navigational paths accessible to all users, Delmont’s 25Black Quotidian instills value in these sources and their open-access availability. By contrast, Brathwaite-Shirley’s Black Trans Archive prompts users to choose between paths whose starting points shift based on whether the user identifies as Black and transgender, transgender, or cisgender. Noting as well that the Black Trans Archive contains no documents—Brathwaite-Shirley builds, instead, on experiences shared with her by Black trans people during interviews that are not included in the public-facing project—students remarked on the artist’s work of accessing a speculative past that is characterized by the violences of misrecognition and denial. By analyzing the ways these two projects converge and separate, students expanded their conceptions of what a Black studies archival project can be and were able to hone their own desires and demands for Black studies archival work.

My courses’ most extensive engagement with collections of Black music took place during fall 2020, when I devoted the entire second course unit to Black music history.26 We also dedicated the final unit to what was then called the African American Sheet Music Collection.27 Hosted on its own website on a Brown Library server, the collection title did not account for the majority of the music contained within it. While it did include works by African American composers like Bob Cole and Will Marion Cook, the collection was primarily a digital repository of blackface minstrel music composed and performed by white people. Other elements of the website amplified the racism that inhered in the title.28 (In the year following my seminar, the website was retired, renamed, and redesigned.29) I will briefly revisit this collection later in the essay while describing my students’ final projects. I believe that assigning texts and repositories like Delmont’s and Brathwaite-Shirley’s and focusing on the relationship between source selection, design, and the production of meaning helped lay the groundwork for students’ expansive responses to the sheet music collection.

Analyzing Digital and Analog Historical Black-Music Anthologies: Three Case Studies

Laura: One outcome of the archival analyses that Sophie undertook with her students was the creation of a scaffold for engaging critically with the anthology case studies that we explored during my sessions. The students’ theoretical grounding and experiences with both metanarratives and archival silences meant that they were well equipped to analyze the commercial and institutional frameworks of the Black-music collections we examined. The case studies served two purposes; each of them presented students an opportunity to explore questions of design, presentation, content selection, organization, and framing in an existing collection that included a significant amount of Black music, while also offering the students content that could potentially be narrated anew in their final projects. Although the collections discussed here differ wildly in their content and presentation, similar questions can be asked of all of them as a starting point for analysis of how the collections’ very constructions imply historical narratives.

Indeed, as Sophie noted, a fundamental premise underlying the courses’ conversations was that the design, description, and organization of collections are not neutral. In other words, the form and presentation of an archive always carry with them some sort of ideological content. Ideology is unavoidable, and students and researchers can create thoughtful, richer historical narratives by understanding the ideological underpinnings of the collections that they use.

This work originally occurred at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, which meant that I was forced to teach the case studies virtually. Given that remote education has since emerged as a form of accommodation and means of enhancing student accessibility, a virtual approach continues to be viable and meaningful. A significant part of teaching the case studies entailed translating analog materials into a context that students could engage with and analyze in a virtual environment. The analog-to-digital teaching experience made me intensely conscious of my role as a mediator and gatekeeper. While under in-person circumstances I do my best to minimize the effects of personal mediation and structural gatekeeping,30 COVID-era restrictions to on-site access made my position as an intermediary between the students and the collections much more palpable. My role as a mediator was one of a number of layers inherent in the processes of narrative construction that we explored in each of the case studies.

1.The Rise & Fall of Paramount Records: Volume One, 1917–1927andVolume Two: 1928–19321. The Rise & Fall of Paramount Records: Volume One, 1917–1927 and Volume Two: 1928–1932

For the fall 2020 iteration of Sophie’s class, I made a series of videos aboutThe Rise & Fall of Paramount Records: Volume One, 1917–1927 and Volume Two: 1928–1932, which are two special editions of sound recordings housed in containers that look like suitcases, and which together constitute an edition of the available output of Paramount Records.31 Owned by a furniture manufacturer, the Wisconsin Chair Company, Paramount was a record label that showcased numerous blues and jazz musicians in the 1920s and early 1930s.32 In my videos, I followed the style of the genre of the “unboxing video” found on YouTube. The COVID-19 pandemic turned the archive where we would typically hold class into a closed-off physical space, so out of necessity, the students had to view the two volumes digitally through my eyes—or rather, through my smartphone’s camera lens—alone.33 At this early stage, I attempted as neutral a stance as possible toward the materials when filming, in part because of my awareness that my virtual presence added a mediating layer between the materials and the students that would not have been there in an in-person experience. What this experience primarily taught me, however, was that neutrality is impossible. Furthermore, the model of the unboxing video led to an emphasis on the materials as products of a business enterprise, which in turn invites a reading of the editions that emphasizes a corporate history of how Black music has been commodified. From a scholarly standpoint, I believe this is one valid reading; but from a pedagogical perspective, it is desirable to find ways of encouraging students to engage a wider range of interpretations that do not immediately present themselves based on the editions’ packaging.

In the videos, I explored the contents of the suitcases in great detail, taking care to include important contextual information such as the physical space in which the collections are housed; the material characteristics of each of the cases; interventions that the Brown Library system had performed on the cases upon acquisition; external materials that Brown had enclosed in the editions; and closely related additional resources. Each of these elements create further layers of mediation that I needed to consider, and encouraged the students to consider, as part of how the process of archivization shaped the tacit narrative surrounding the collection. For each video, I then removed and reviewed the items from the suitcases in the order in which they presented themselves. The contents included many different forms of advertising materials, sheet music that would have been used in a sales context, a “field manual,” a coffee-table book about the history of Paramount, and recorded music in anachronistic formats such as 33 ⅓-rpm discs and USB drives—all with luxuriant production values. The twin emphases are on the recording company, Paramount Records, and its parent company, the Wisconsin Chair Company; and on the production values of the material items themselves as present-day collectables.

The Paramount suitcases suggest a number of challenging questions that one could pose to students for discussion and evaluation. As noted above, I believe that the suitcases themselves present a packable and portable vision of the music by highlighting the commodification of the blues through the eyes of, potentially, a traveling salesman, or perhaps the consumers that he engaged with. And the assemblers of the suitcases certainly emphasize the commodity status of the music at hand.34 As consumers of the cases, we are encouraged to regard the music produced by Paramount through media such as sales material as well as through the lavish (and nostalgic) contemporary commentary found in the editions’ enclosed books. In short, the narrative frame instantiated by the suitcases encourages a reading that privileges corporate history and commodification. In order to create a different history with these materials, students would need to deconstruct the narrative and put the individual items into a different kind of dialogue.

2.Goodbye, BabylonandGood News: 100 Gospel Greats2. Goodbye, Babylon and Good News: 100 Gospel Greats

In the summer of 2021, Sophie and I became interested in taking a new approach to questions of how music collections create narratives. I engaged with this idea in two ways; I will discuss the first in the current section, and the second in the third case study below. The first was comparative: we selected two smaller collections of music in the same genre that, as I discovered, had overlap in content, and then we analyzed the differences in how narratives were constructed by the packaging and arrangement of materials. With input from Sophie, I selected two anthologies of American gospel music:Goodbye, Babylon and Good News: 100 Gospel Greats.35 These anthologies were, due to their cataloging, next to each other on the shelf in the Orwig Music Library collection, suggesting a relationship through physical proximity.36 However, examination of the construction of these two anthologies revealed strikingly different approaches to the creation of a narrative of gospel music through selection and organization. 36

In class, we framed our discussion of these collections around a series of questions:

- How do these compilations attempt to define and delineate the story of, for example, a genre?

- How do these collections define “gospel music”?

- What are the organizing principles that underly these collections?

- What stories do they tell through their organizing principles?

- How do the writers of the liner notes suggest or imply networks of communication and community between the creators of these genres?

- According to these writers/compilers, who has agency in creating, altering, and defining gospel as a genre? How does that creation, alteration, and definition occur?

- What stories can we tell by having collections “speak” to each other?

By engaging these questions—and questions students brought themselves—we facilitated an entry point into narrative analysis.

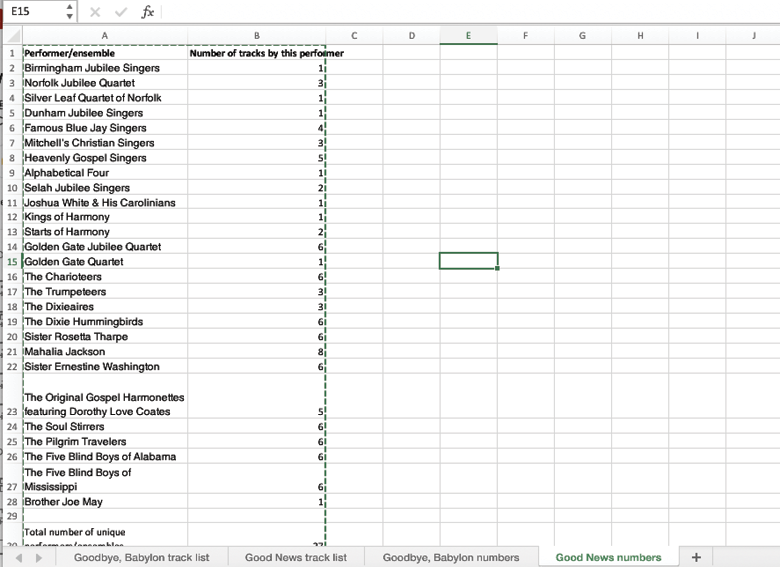

To prepare for these discussions, I evaluated the contents ofGoodbye, Babylon and Good News by detailing the pieces and performers represented in them and then grouped and ordered the contents in a spreadsheet (figure 1).

My initial examination of the collections showed a major difference in the sheer number of performers presented, and the order in which they and their works appeared. To supplement this analysis, we made the liner notes for both collections available to the students.

As with the Paramount suitcases, packaging and presentation were integral to our analysis of the collections’ narrative frames.Good Newsfeatures the same image repeatedly in its packaging: a photo of a crowd of Black people outside of a building, possibly a church. There are a handful of images in theGood Newsliner notes, all of which are of people named in the notes, and all of them Black. This collection thus conveys that gospel is a Black genre of music, one promulgated by its “great” (cf. the title) practitioners.Goodbye, Babylon’s packaging and imagery suggest something quite different, and require background research to be fully comprehensible: there is a multiplicity of interpretive frames, which are somewhat grounded in religious practice, and which interleave Black and white performers.Good News features the same image repeatedly in its packaging: a photo of a crowd of Black people outside of a building, possibly a church. There are a handful of images in the Good News liner notes, all of which are of people named in the notes, and all of them Black. This collection thus conveys that gospel is a Black genre of music, one promulgated by its “great” (cf. the title) practitioners. Goodbye, Babylon’s packaging and imagery suggest something quite different, and require background research to be fully comprehensible: there is a multiplicity of interpretive frames, which are somewhat grounded in religious practice, and which interleave Black and white performers.37 37

The In Good News, twenty-seven individual performers or groups are represented on one hundred tracks. All works by the same artists are found together, which puts an emphasis on the output of those artists while being framed as exemplars of the “greatness” indicated by the collection’s title. All of the selections are by Black performers, thus also framing gospel as a Black musical genre. That the selections are arranged chronologically lends itself to a time-based narrative progression through gospel’s “greatest” practitioners.38 By contrast, 38Goodbye, Babylon has a more complicated organizational structure and different selection criteria. Its goal is to “reflect the regional and cultural varieties of Protestant liturgical music” from the late 1920s into the 1950s.39 Within that context, 140 individual performers, performing groups, and speakers are represented on 160 tracks. Very few performers are represented more than once, and the ones who are represented more than once are not grouped together, which discourages any focus on them as exceptional.40 Black and white performers and groups are intermixed throughout the collection without commentary about the racial dynamics that may have been at work. This organizational principle has the effect of telling a story of the genre as part of a cultural discourse that crossed racial boundaries—a narrative that is completely at odds with the framework of 40Good News.41

By enumerating the contents comparatively and analyzing the organization of the collections, we identified a clear and fundamental difference between the ways the collections present a narrative of gospel music: in one instance, we find a chronology of exceptionalism in a Black musical genre and, in the other, a genre that crossed racial boundaries and was part of a larger enterprise of recorded sacred musics. Three-and-a-half instances of overlap occur between the two collections: three of exactly the same songs in both collections, and one instance in which there are different recordings of the same song by the same performer. An exercise for class discussion would be to examine the differences in how those specific works are presented in each collection as another way of discerning how the narratives collide or diverge when the material is not just similar but precisely the same.

The point here is not to demonstrate that one collection gets history more right than another—each organizational scheme has benefits and pitfalls—but rather to encourage students to appraise how processes of selecting and placing material into organizational schemes are themselves acts of creation.42 This exercise demonstrates not only that these collections create different versions of the history of the music; it demonstrates how packaging, selection, and organizational choices then drive the framework—the narrative and metanarrative—according to which each collection tells a story. Following this exercise, students were again encouraged to take individual selections from these and other collections and recombine them to formulate new narratives—thus placing the power of retelling history in their hands.

3. The National Jukebox and Other Digital Collections Including Black Music

Finally, we looked at online archives that include Black music, with a similar goal of exploring how the selection and design processes that shape a given collection affect how we encounter and understand its content. The Library of Congress’s National Jukebox consists of digitized recordings from the 78-rpm format and record labels from which the Library of Congress received permission to digitize. It is a potentially rich source of information about Black music, even while it is far from exclusively an archive of said music.43 Upon its launch in 2011, the National Jukebox primarily included recordings made by the Victor Talking Machine Company from between 1901 and 1925, although there had also been a plan to add materials from labels owned by Sony Records. The underlying framework for the existence of this digital collection was an understanding that had been reached in 2008 between the Library of Congress and Sony, supplemented by additional partnerships with the University of California, Santa Barbara, EMI Music, and two record collectors, David Giovannoni and Mark Lynch.44 Thus the National Jukebox represents an intersection of corporate, collector, and institutional interests, coordinated and constructed by a US Government agency.

The starting point for exploring the National Jukebox collection is through its web interface, found (as of when we taught the classes and subsequently) athttps://www.loc.gov/collections/national-jukebox—into the approximately 16,000 recordings in the collection were limited, and in some cases yield fewer results than the research might expect.45 For example, there were fifty-three entries in the category “target audiences,” although the majority of the recordings have no target audience data, suggesting that it is a metadata concept that was either abandoned or for which there weren’t resources or information to execute fully. The recordings were categorized into forty-four genres, although more than half of the recordings were simply labeled “popular music.” A recording can belong to more than one genre in the catalog. Other entry points into the collection include the names of specific artists and the names of recordings; while such an organizational approach can yield rich results, it nevertheless requires that students perform preliminary research to determine what they are looking for. For example, a search for the performer Bert Williams (1874–1922) brings up roughly thirty-five recordings, the majority of which are categorized under the umbrella “popular music” designation. A search for the singer Bessie Smith yields thirty-four results, thirty-three of which are in the genre category “blues.” These results reinforce that, while genre can be useful, it remains an incomplete and potentially confusing lens for discovering music by Black performers; yet no other easily used alternatives present themselves in this resource.46

The interface’s framing for each recording in the collection is relatively sparse: the website’s navigation includes a playback bar for the selected recording; an image of the physical label from the 78-rpm record; data about a recording’s title and performers; and supplementary information about the size of the disc, record label, catalog number, matrix number, take number, recording location, and more. The focus is thus on the physical disc and the circumstances surrounding the creation of the 78-rpm recording. Individual, cultural, and even corporate histories are (eerily) absent; the technological narrative and the material discs and their transformation into digital entities are foregrounded. In addition, although a more fully “national” jukebox is now a greater possibility due to revisions in copyright law, for the moment, students should remain cognizant of how the jukebox’s framing is limited by earlier legal restrictions and the Library of Congress’s agreements with corporate entities. In short, this collection narrates a material, technological, and legal history; in order to reorient these recordings toward the context of the music and its creators, students would need to do a significant amount of background research on each piece as they consider what it would mean to construct a new collection.

4. Reflection

In individual class sessions, Sophie and I worked together to explore the examples given here and imagined what a longer-term project that evaluates the much larger quantities of material in streaming archives might entail and accomplish. We tended to approach these collections by drawing attention to the materialities of the original media or the technical aspects of either the original recording or the digitization process, elements that can be highlighted by unpacking (literally or figuratively) the design of overall collections or information about individual items. In all of the cases, the presence of corporate history was strong, reflected either in the content of the collection or in the circumstances of the collection’s creation. Imagining other narratives of Black music history may well first entail conceiving of its content disentangled from the processes of commodification and corporatization; or, it may entail exploring why they cannot be disentangled. In our class sessions, we encouraged students to consider the gap between the lived experiences and perspectives of the music creators and the repackaging of their creations and experiences into collections and commodities, in part by referring to the critical scholarship explicated above, notably the work of Hamilton and Brooks. This line of inquiry opens a space to think about things that are not represented in the collections that currently exist, and for students to contemplate how they might construct a representation of what is missing.47

As the current manager, and, in a sense, inheritor, of a music library’s collections, I find both omissions in said collections—driven by a number of factors, including but not limited to the historical and current research interests of the community, budgetary considerations, and whether materials even exist to be acquired—and the narratives created by the organization and framing of the existing collections to be vexing and urgent problems. Both omissions and narrative structures accumulate over time, and changing them is a necessary but slow process; large-scale reorganization projects require, at a minimum, significant staff time to conceptualize and implement, ideally would incorporate community input, and may require changes at the level of facilities or institutional structures. Thus the power of an instructional approach like the one described here; this process invites and encourages the next generation to reimagine collections and their stories, and can be implemented relatively rapidly.48

In the remainder of this article, Sophie reflects on her student projects, and we both think through the outcomes and implications of our collaboration.

Student Projects

Sophie:It was through multimodal close analyses like Laura’s case studies—and through short web-building assignments—that I prepared students for their final project: using primary source items from a physical or digital collection to create their own dynamic online archive in the web-based publishing program Scalar.Working alone or in pairs, I asked students to draw on materials of their choosing from a given archive or collection in order to analyze and create a digital representation of their items of choice. In groups, students collaboratively drafted a series of project statements and designed web pages and navigational pathways. Over the years, classes have produced digital archives with introductions, collection histories, land acknowledgments, and positionality statements. In the sections of each class project that were focused on item analysis, students’ individual writing has often spanned multiple pages and incorporated embedded images, alt text, hyperlinks, and interpretation of aspects that cannot be contained in the digital frame.Sophie: It was through multimodal close analyses like Laura’s case studies—and through short web-building assignments—that I prepared students for their final project: using primary source items from a physical or digital collection to create their own dynamic online archive in the web-based publishing program Scalar.49 Working alone or in pairs, I asked students to draw on materials of their choosing from a given archive or collection in order to analyze and create a digital representation of their items of choice. In groups, students collaboratively drafted a series of project statements and designed web pages and navigational pathways. Over the years, classes have produced digital archives with introductions, collection histories, land acknowledgments, and positionality statements. In the sections of each class project that were focused on item analysis, students’ individual writing has often spanned multiple pages and incorporated embedded images, alt text, hyperlinks, and interpretation of aspects that cannot be contained in the digital frame. 49

In 2020, half of the students in my “Collections and Colonialism” seminar worked together to create the digital archival project Making Minstrelsy: Late 19th- and Early 20th-Century African American Sheet Music.50 Making Minstrelsy is a curated online collection created out of materials housed in the larger digital archive that Brown now calls Representations of Blackness in Music of the United States (1830s–1920s).51 From this larger archive, students developed elements featured in their own collection that worked against the grain of hegemonic racist depictions of Blackness in popular sheet music of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and celebrated creative Black futurity through aesthetic, materialist, historiographical, and sonic analyses. 51

While I was deeply impressed by students’ willingness to both learn and adapt the tools of the online platform—embedding sheet music with a page-turning function, for example, and coding images with alt text in different alignments on each page—I was especially taken by their decision to deconstruct those same affordances. Scalar functions as a digital book: users navigate the website by using either a dropdown table-of-contents menu in the top left corner of each page or a landing page that scrolls downward. At the bottom of each web page is an option to click forward and “turn pages” in numerical order. In order to resist the structural pressure to create a linear progression out of a layered, muddled, and abundant history, students created a system of page “tags” (figure 2). Beneath each list of works cited in the collection, a series of tags acts as a kind of word cloud that produces multiple connections between different item analyses. Each student focused on one primary source item through the lens of Black futurity. They organized their site navigation such that users can elect to follow the progressive path of one tag by clicking a “continue” button, or to jump around the site using a different tag. Each tag or grouping mechanism refigures the possibilities that each item page opens up. In this way, students foregrounded Trouillot’s “active act of production” at every entry point to the collection.52 52

I have found that spending time discussing various methods of organizing a collection, breaking into small groups, and then producing word clouds like those represented in Making Minstrelsy helps students build interpersonal relationships and trust in both large and small classroom contexts, while also encouraging them to embrace the many ways that historical narrative can be shaped. As evidenced by Making Minstrelsy, this kind of collaborative and interrogative thinking also helps produce dynamic multimodal work.

Digital, critical, and speculative archival assignments ask students to incorporate their multivalenced analyses from across the semester into a sui generis project; to use design to critically consider how visual, textual, and audible forms affect a user’s engagement with archives and collections; to build community with their peers; and to imagine the kind of world that can be constructed by creatively producing history in archives and collections. Back in person in 2022, my “Collections and Colonialism” seminar met these challenges in form and content through what they named the Hazel Carby Papers Web Project: an experimental, collaborative, and digital archival project based on the recent acquisition of the Hazel V. Carby papers in the Feminist Theory Archive at the Pembroke Center for Teaching and Research on Women.53 While graduate students in the course pursued projects on their own, ten advanced undergraduates joined together to create a collection characterized by experimentation and care. As in my 2020 seminar, students decided to leave the Hazel Carby Papers Web Project unpublished. I found that this decision diffused the pressure of having a project permanently available online, which then allowed students to take more risks and, according to some of their reflections, feel less anxious about their work. I also found that assigning an archive that was not fraught by the explicit racism of the sheet music collection opened up more space for personal and creative engagement with the primary source material. Immersion in the personal and pedagogical papers of a brilliant and dynamic Black feminist scholar also energized students’ work. This kind of archive is more often available at well-endowed research institutions. However, academic archivists and librarians are creative and resourceful across universities, and with time and planning, it is possible to draw from multiple collections—within the library and even at local museums and historical societies—to curate sources for students to explore a topic for which contents are not apparently available.

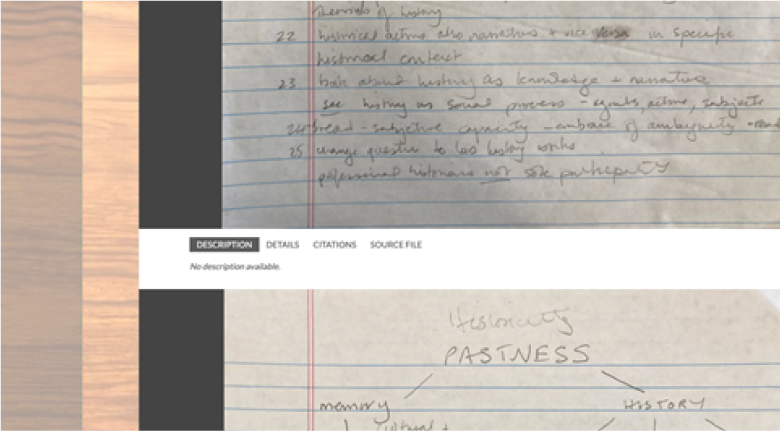

The successes of this particular assignment were conspicuous in student Zoe Kupetz’s “Notes on Silencing the Past.” In her work, Zoe offered “a web or a woven fabric” as a formation through which to access what she calls Carby’s Black feminist intellectual genealogy building.54 Drawing on that very genealogy in her analysis of it, “Notes on Silencing the Past” demonstrates how Zoe thought explicitly alongside her peers, the theorists and historians we had read throughout the seminar, and Carby’s own chosen interlocutors. In her piece, Zoe selected material that was similarly composed of layered and interlocked voices. At the time, she was training to be a history teacher, and focused her project on three pages of notes that Carby wrote to prepare to teach Trouillot’s54 Silencing the Past in a seminar. Rather than just analyzing the notes, Zoe wove together online course information for Carby’s seminar that included Silencing the Past itself, transcriptions of the reflective “closing questions” that Carby asked her students to write her at the end of that seminar, written responses from one of Carby’s students (now a professor herself), the foreword Carby wrote for the 1995 edition of Trouillot’s book, and photographs of Carby’s notes on Trouillot’s text (figures 3 and 4).

Zoe also webbed her web design as a series of formal, personal, and interpersonal choices, and by expanding the particularities of Carby’s intertextual work by means of analyzing and adapting them to her own pedagogical project, Zoe created an archive of legacy and care (figure 5).

I believe that the final project provoked this level of depth and engagement because Laura and I spent the semester introducing students to creative, rigorous, and multimodal approaches to collection design, description, and analysis. And so students were prepared to participate in that project themselves. Grappling with histories of resilience—as with histories of violence, which are so often intertwined—requires an environment of care and trust. Small-group discussions, student-led presentations, forthright conversation, and un-grading all contributed to the project’s success.55

Conclusions

Sophie: Creating an environment of trust is not limited to the relationship between students and instructor; it extends as well to instructor collaboration. Our collaboration worked so well because we were able to think through Laura’s role in the course while I was still finalizing it. The long-term nature of our work together also allowed us to check in throughout each semester. Brainstorming and planning together in an extended and active way forced me to hammer out the curvatures of the final project and the arc of the semester to ensure that we were driven by the same questions and goals leading into students’ creation of dynamic, collaborative digital archives. Our shared experience also reinforced our profound investment in collaborative, interdisciplinary teaching: my courses did not need to focus exclusively on music to provoke deep, sustained engagement with digital and physical anthologies, for example, and in fact Laura’s facilitation of students’ close engagement with the affordances of each collection’s construction encouraged the same level of analysis of how different digital and physical repositories engage with Black history. Laura’s focus on the questions posed by and through Black-music anthologies in particular also resonated throughout the semester, and appeared pronouncedly in the ways students recombined and reimagined elements of the sheet music collection at Brown.

Sophie: Creating an environment of trust is not limited to the relationship between students and instructor; it extends as well to instructor collaboration. Our collaboration worked so well because we were able to think through Laura’s role in the course while I was still finalizing it. The long-term nature of our work together also allowed us to check in throughout each semester. Brainstorming and planning together in an extended and active way forced me to hammer out the curvatures of the final project and the arc of the semester to ensure that we were driven by the same questions and goals leading into students’ creation of dynamic, collaborative digital archives. Our shared experience also reinforced our profound investment in collaborative, interdisciplinary teaching: my courses did not need to focus exclusively on music to provoke deep, sustained engagement with digital and physical anthologies, for example, and in fact Laura’s facilitation of students’ close engagement with the affordances of each collection’s construction encouraged the same level of analysis of how different digital and physical repositories engage with Black history. Laura’s focus on the questions posed by and through Black-music anthologies in particular also resonated throughout the semester, and appeared pronouncedly in the ways students recombined and reimagined elements of the sheet music collection at Brown.

In Harlem Is Nowhere, an autoethnographic masterpiece of history, cultural theory, and biography, Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts writes of what she calls “an unnatural history”: a story of places that exist as if they have always been one way when, in fact, they mask a mix of various beginnings.56 Across my courses, my goal as a college instructor has been to give undergraduate and graduate students the tools with which to demythologize their environments, and to bring new narratives to life. By importing this goal into the analysis of digital and physical archives and collections of Black music and Black history—both foundational sites of historical production—we encouraged students to collaboratively engage with the ways that power has reconstructed the world in its favor on the one hand, and on the other hand, the ways that people suffuse the world with meaning against and outside of these dangerous forms of production. If students can reimagine the ways that history is produced at the moments of its rearticulation, then the present becomes a site of possibility. This kind of creative and communal thinking and building was the goal of our shared pedagogical work.

- This is a quick distillation of a complex network of decision making. The influences of this network of people, positionalities, and desires—as well as of collecting trends, labor concerns, and institutional and digital affordances—are manifest in the visual and navigational profiles of any digital archive.[↩]

- While Sophie’s job was technically at the Center for Digital Scholarship, she also worked in different capacities with the John Hay Special Collections Library and the Pembroke Center for Teaching and Research on Women.[↩]

- The exception was a summer iteration of “Collections and Colonialism,” which had only four students; this situation is highly unusual.[↩]

- The topic of how archives shape historical narrative has been widely discussed, most pertinently in Antoinette Burton, Archive Stories: Facts, Fictions, and the Writing of History (Durham, DC: Duke University Press, 2005). This approach resonates with the “Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy,” developed jointly by the Association of College and Research Libraries’ Rare Book and Manuscript Section and Society of American Archivists, and approved in 2018 by the ACRL Board of Directors and Society of American Archivists Council, https://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/standards/Primary%20Source%20Literacy2018.pdf. See specifically the document’s passages regarding interpretation, analysis, and evaluation.[↩]

- On these matters, see Burton, Archive Stories, 1–24, esp. 5, in which Burton references Tina Campt on the dialogue of minute and monumental archives.[↩]

- Marybeth Hamilton, In Search of the Blues (New York: Basic Books, 2008); Daphne A. Brooks, Liner Notes for the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021).[↩]

- As Hamilton writes, “Revivalists privileged an obsolete form of rural black culture in an era when most African Americans lived in cities, and towards contemporary black music they displayed at best ambivalence, more often hostility.” Hamilton, In Search of the Blues, 239. On genre and racial history, especially in popular music, see for example Maureen Mahon, Black Diamond Queens: African American Women and Rock and Roll (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020), 1.[↩]

- Brooks also notes that the collections of 78s from which amateur collectors gathered materials were assembled by Black music listeners, often women, who were usually rendered invisible in subsequent discourse on the topic. See Brooks, Liner Notes for the Revolution, 291–93.[↩]

- Will Straw, “Sizing Up Record Collections: Gender and Connoisseurship in Rock Music Culture,” in Sexing the Groove: Popular Music and Gender, ed. Sheila Whiteley (New York: Routledge, 1997), 5. Straw’s work also notes the domination of record collecting by males, but problematically refrains from subjecting to adequate critique Frederick Baekeland’s essentializing alignment of male collecting with the “historical” domain and female collecting with the “personal and ahistorical” realms. See Straw, 6.[↩]

- For an example of a woman, specifically Rosetta Reitz, who collected “against the grain,” see Brooks, Liner Notes for the Revolution, chapter 3.[↩]

- My discussion here is far from exhaustive. A more thorough exploration of this topic would be a welcome addition to the scholarship.[↩]

- James Haskins, Black Music in America: A History through its People (New York: Crowell, 1987). On criticism of the “genius” paradigm, see Evan Williams, “The Myth of the Composer-Genius,” March 27, 2019, https://icareifyoulisten.com/2019/03/the-myth-of-the-composer-genius/.[↩]

- Mellonee V. Burnim and Portia K. Maultsby, eds., African American Music: An Introduction, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2015).[↩]

- For example, see Mahon, Black Diamond Queens, 1. For a cogent discussion of the shifting nature of genre in popular music over time, see David Brackett, Categorizing Sound: Genre and Twentieth-Century Popular Music (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016), chapter 1.[↩]

- An example highly relevant to the discussion below is Alex van der Tuuk, Paramount’s Rise and Fall: A History of the Wisconsin Chair Company and Its Recording Activities (Denver: Mainspring Press, 2003). Another pertinent set of examples includes the multiple extant anthologies of the output of the Motown record label, such as Hitsville USA: The Motown Singles Collection 1959–1971, Motown Records, 1992; and The Complete Motown Singles Collection, Motown Records, 2008.[↩]

- For example, see Samuel A. Floyd Jr., “Black Music and Writing Black Music History: American Music and Narrative Strategies,” Black Music Research Journal 28, no. 1 (2008): 111–21; and The Power of Black Music: Interpreting Its History from Africa to the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995).[↩]

- See Floyd, “Black Music and Writing Black Music History,” 113–17.[↩]

- Daniel Barolsky, “Performers and Performances as Music History,” in The Norton Guide to Teaching Music History, ed. C. Matthew Balensuela (New York: W. W. Norton, 2019), 159.[↩]

- In the order that they appear in the body of this essay, the texts that I assigned to my seminars include: Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (New York: W. W. Norton, 2019); Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016); Margaret Kovach, Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Frameworks, Contexts (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2021); Lisa Brooks, Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019); Marisa Elena Duarte, Network Sovereignty: Building the Internet Across Indian Country (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017); Kim Gallon, “Making A Case for the Black Digital Humanities,” in Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016, ed. Matthew K. Gold and Lauren F. Klein (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016), 42–49; Jessica Tai, “The Power of Words: Cultural Humility as a Framework for Anti-Oppressive Archival Description,” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 3, no. 2 (2021); and Jarret M. Drake, “‘Graveyards of Exclusion’: Archives, Prisons, and the Bounds of Belonging,” Medium, March 24, 2019, https://medium.com/community-archives/graveyards-of-exclusion-archives-prisons-and-the-bounds-of-belonging-c40c85ff1663. Two guest speakers assigned two of the listed texts during their classes: Jax Epsten, MLIS (Tai) and Dr. Alyssa Collins (Gallon).[↩]

- Sophie Abramowitz and Elli Mylonas, “Approaching Site Models,” Digital Scholarship Resources for Courses Guide, Brown University Library, 2021, last updated September 11, 2024, https://libguides.brown.edu/c.php?g=1049232&p=8940924.[↩]

- Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (New York: Penguin, 2015), 52–53.[↩]

- Trouillot, 52.[↩]

- See, for example, Michelle Caswell, Urgent Archives: Enacting Liberatory Memory Work (New York: Routledge, 2021); Emily Drabinski, “Queering the Catalog: Queer Theory and the Politics of Correction,” The Library Quarterly 83, no. 2 (April 2013): 94–111; Jarrett M. Drake, “RadTech Meets RadArch: Towards a New Principle for Archives and Archival Description,” Medium, April 6, 2016, https://medium.com/on-archivy/radtech-meets-radarch-towards-a-new-principle-for-archives-and-archival-description-568f133e4325#.w1a50egi; Verne Harris, Archives and Justice: A South African Perspective (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2007); Randall C. Jimerson, Archives Power: Memory, Accountability, and Social Justice (Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2009); Mario H. Ramirez, “Being Assumed Not to Be: A Critique of Whiteness as an Archival Imperative,” The American Archivist 78, no. 2 (2015), 339–56; “Cultural Framework,” Society of American Archivists Cultural Heritage Working Group, Society of American Archivists, accessed July 12, 2020, https://www2.archivists.org/groups/cultural-heritage-working-group/cultural-framework; and Sam Winn, “The Hubris of Neutrality in Archives,” Medium: On Archivy, April 24, 2017, https://medium.com/on-archivy/the-hubris-of-neutrality-in-archives-8df6b523fe9f.[↩]

- Rather than using deconstructive and critical reading as the end goal of analysis, I have found that students are interested in using these practices as components of collaboration and constructive thinking. I credit my students at Brown University for continually pushing our seminars toward these goals.[↩]

- Matthew M. Delmont, Black Quotidian: Everyday History in African-American Newspapers (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2019), web page updated September 16, 2020, https://mattdelmont.com/2020/09/16/black-quotidian/; Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, “Black Trans Archive,” 2021, https://blacktransarchive.com/.[↩]

- The seminar’s second unit focused on the frenetic, obsessive history of white collectors of early twentieth-century Black recorded music, and on Black artists and collectors producing imaginative new paradigms of compiling Black history. Texts included Hamilton, In Search of the Blues; Hari Kunzru, White Tears (New York: Knopf, 2017); Daphne A. Brooks, “See My Face From the Other Side,” Oxford American 95 (Winter 2016), https://oxfordamerican.org/magazine/issue-95-winter-2016/see-my-face-from-the-other-side; John Jeremiah Sullivan, “The Ballad of Geeshie & Elvie,” New York Times, April 13, 2014; Simone Leigh, “The Chorus,” Raid the Icebox Now, RISD Museum, July 22, 2021, https://publications.risdmuseum.org/raid-icebox-now/simone-leigh-chorus; and selected writing and recordings by Zora Neale Hurston.[↩]

- I chose this collection because I received my job offer during the summer and joined the university remotely. I therefore had neither the time nor the ability to gather options for my students. Instead, I relied heavily on the help of Dr. Holly Snyder, then Brown’s Curator of American Historical Collections and North American History Librarian, to figure out which collection would best suit the needs of my class. That same semester, half the class worked with the Collection and half designed their own group project. In the following semesters, I was able to give my students an array of final project collection options.[↩]

- For example, the landing page of the website features a prominent representation of a Black child that engages with visual tropes of minstrelsy and the website lacks content warnings. This iteration of the collection display does, however, historicize blackface minstrelsy in its “About” and “History & Context” sections.[↩]

- The website has been migrated to the Brown Digital Repository, given new introductory text, and appropriately renamed Representations of Blackness in Music of the United States (1830s–1920s). It is accessible at https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/collections/id_555/. The retired, static African American Sheet Music Collection website is still linked on the homepage of the new website, at https://library.brown.edu/cds/sheetmusic/afam/.[↩]

- Of course, these are also decisions on my part that have an ideological basis.[↩]

- Paramount Records—The Rise and Fall: Volume One, 1917–1927 (2013) and The Rise & Fall of Paramount Records, Volume Two: 1928–1932 (2014), compiled by Alex van der Tuuk, Jack White, and Dean Blackwood, released by Third Man Records and Revenant Records, 2013–14.[↩]

- For an in-depth discussion of the process of assembling the Paramount suitcases, see Edward Komara, “Suitcases Full of Blues: The Revenant/Third Man Paramount ‘Cabinets of Wonder,’” ARSC Journal 46, no. 2 (2015): 217–44. Note that Komara himself played a role in preparing the collection. Komara clarifies that the USB drives in the suitcases do not include the full output of the Paramount label, as there are outstanding titles with no 78-rpm copy found.[↩]

- At the height of the pandemic, the music library was closed to everyone but myself and one other staff member.[↩]

- Komara clarifies that these cases could also be read as portable record players, another reference back to the records’ corporate origins in a furniture company. See Komara, “Suitcases Full of Blues,” 227.[↩]

- Goodbye, Babylon, compiled by Lance Ledbetter, with essays by Charles Wolfe, Dick Spottswood, and David Warren Steel, Dust-to-Digital, 2003; Good News: 100 Gospel Greats, Proper Records, 2002.[↩]

- The sound recording collections at the Orwig Music Library are classified according to the Library of Congress scheme, which indicates that materials in proximity are, more or less, on the same subject, which here is closely related to genre.[↩]

- The exterior box for Goodbye, Babylon is made out of wood, with a sliding lid—perhaps a nod to a Bible box. The image printed on the box is based on Gustave Dore’s religious painting The Confusion of Tongues (c. 1868), which portrays the Tower of Babel rather than any Biblical stories about Babylon. In short, the box itself is a gesture toward the materialities of religious practice. The box also includes two tufts of cotton, in a clear nod to the agricultural American South. The cover of the liner notes takes its cues from the Sacred Harp tradition, including layout and numerous phrases taken directly from the cover of the shape-note tune book “Original Sacred Harp” (1911). “Original Sacred Harp” was itself framed according to a narrative of white American sacred music, which can be easily discerned through its enclosed pictures of the all-white, all-male committee that compiled and revised the collection and its admonition against “the twisted rills and frills of the unnatural snaking of the voice, in unbounded proportions”—quite possibly a reference to Black singing styles—in the preface. See “Preface,” in “Original Sacred Harp” (Atlanta: J. S. James, 1911), III. It is clear, however, that Sacred Harp singing was also a significant practice in Black congregations from the 1880s onward. See Joyce Marie Jackson, “Quartets,” in African American Music: An Introduction, ed. Mellonee V. Burnim and Portia K. Maultsby, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2015), 80–81.[↩]

- Disc one includes recordings from 1926–49; disc two, 1937–50; disc three, 1938–51; and disc four, 1946–51. The selections are arranged chronologically by recording date within subgroups of songs organized by performer/performing group.[↩]

- Dick Spottswood, “Introduction,” in Goodbye, Babylon, iii. It is unclear how much “regional” variety is represented, since most of the performers appear to have come from the US Southern states, even if they recorded in locations such as Grafton, Wisconsin (home to Paramount Records).[↩]

- I use the word “exceptional” here in the sense of “exceptionalism,” in other words, a framework according to which specific individuals and their work are regarded as superior and thus the only content worthy of study.[↩]

- It merits noting that, within the music sections of the collection, each disc has its own thematic and narrative frame: disc one is “Introduction”; disc two “Deliverance will come”; disc three “Judgment”; disc four “Salvation”; and disc five “Goodbye, Babylon.” As a whole, therefore, the music collection constructs a salvation narrative. The final disc, which consists of sermons, might serve to illustrate how sacred music integrated into larger religious practices, although the collection notes indicate instead that the sermons were “assembled on the premise that the cadences of Southern liturgical oratory contain music of their own.” Spottswood, iii.[↩]

- For example, the “genius” paradigm has the advantage that it can offer a portrait of an individual’s or group’s development over the course of a career, making previously marginalized musicians better known. The salvation narrative collection, on the other hand, has the advantage of contextualizing the music firmly in religious practices, an aspect that is almost entirely lost with the genius narrative.[↩]

- Brown has access to a number of subscription-based music services that incorporate Black music, including the Black-focused streaming video database Qwest.tv.edu. However, since the student projects were intended for dissemination, we needed to look for digitized materials that came laden with fewer licensing restrictions than is typical of subscription services.[↩]

- See “News Briefs,” Library Journal, January 2011, 46; and “Partners,” Library of Congress, accessed February 20, 2023, https://www.loc.gov/collections/national-jukebox/about-this-collection/partners/. Although there was a change in music copyright law in 2022, which had the potential to put a great deal of early 78-rpm music in the public domain, I have not heard of any plans to greatly expand the National Jukebox.[↩]

- These searches and search results are as of summer 2022; both the content and the interface may have changed by the time this article is published.[↩]

- For example, the genre term “Ragtime, Jazz, and More” pulls up a list of recordings by non-Black performers such as Frank Guarente and Frank Westphal.[↩]

- I make this observation in light of Floyd’s indication that “documented and documentable facts” should not be the only “grist for the scholarly mill.” Floyd, The Power of Black Music, 268.[↩]

- Michelle Caswell’s work is also relevant to the idea of deconstructing archival narratives, although I believe our work takes the next step by encouraging students to then construct something new from that which has been deconstructed. See Michelle Caswell, “Teaching to Dismantle White Supremacy in Archives,” The Library Quarterly 87, no. 3 (July 2017): 222–35.[↩]

- The first two iterations of this seminar were limited to digital collections because courses at Brown were held remotely in the beginning of the pandemic. The third iteration of the course focused on digital collections throughout the semester, but the final project required in-person visits to a physical collection. To familiarize themselves with Scalar, each class worked throughout each semester with either Elli Mylonas or Patrick Rashleigh from Brown University Library’s Center for Digital Scholarship.[↩]

- One half of “Collections and Colonialism” elected to build a digital collection in Scalar; the other worked on a different digital group project. For the purpose of this essay, I focus only on the music-related project.[↩]

- Representations of Blackness in Music of the United States (1830s–1920s), Brown Digital Repository, accessed October 21, 2024, https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/collections/id_555/.[↩]

- Trouillot, Silencing the Past, 52.[↩]

- At the time of teaching this seminar, I was also processing these papers as an archival assistant to Amanda Knox. The finding aid to The Hazel V. Carby Papers, 1972–2016, is now available at https://www.riamco.org/render?eadid=US-RPB-ms… All images represented from this collection can be found in the Hazel V. Carby papers, MS.., Pembroke Center Archives, John Hay Library, Brown University.[↩]